When it comes to life, the issue of quantity versus quality is frequently debated. As it turns out, doctors have come down overwhelmingly on the side of quality…but alas, only for themselves. When it comes to your life, quantity rules the day. This is not idle speculation. Around a decade ago, I wrote about a survey among doctors that showed that most doctors–especially oncologists, would not choose chemotherapy for themselves or their families as an end-of-life option. This was especially interesting since it’s the same treatment they try and strong arm their patients into–periodically, even calling in the courts to force their patients into compliance.1 “Judge orders chemotherapy for 13-year-old cancer patient.” CNN.com/US May 26, 2009. (Accessed 18 April 2014.) http://www.cnn.com/2009/US/05/26/minnesota.forced.chemo/index.html An interesting double standard, yes?

I always liked the survey since it reinforced one of the major reasons I walked away from premed and turned to alternative medicine. Let me talk about that experience briefly, and then get back to the report.

The Doctors and My Grandmother, a Drama in 4 Acts

Back in the late 60’s, I was visiting home, back from college on a break. At that time, I was still premed.

Act 1

While home, I went with my father to visit my grandmother, who at that time, even though she was in her early 90’s, was living by herself. Until she broke her hip in her late 80’s, she had been a force of nature, strong and fiercely independent. After the hip, she was diminished, but still fiercely independent. Anyway, while visiting her, it was readily apparent that something had changed drastically over the last couple of days. So against her strong protests, we took her to the hospital emergency room.

After waiting for a couple of hours for them to see her and then a couple more waiting for them to finish, they returned with the verdict that nothing was wrong and that she should go home and get some rest. My father and I vehemently objected to their diagnosis, telling them it was impossible; but it wasn’t until we threatened to hold them liable if they had screwed up and she suffered for it that they agreed to reexamine her.

This time, it was only about 30 minutes later that they reappeared in a panic. On closer examination, they had discovered that she had recently suffered several heart attacks and had gangrene in her leg. She had to be admitted to the hospital post haste. Gotta love it. Incidentally, misdiagnosis is far more common than you might think.

Act 2

The next day, when we went to visit her in the hospital, the doctor pulled my father aside before we even entered her room and told him they needed to amputate my grandmother’s leg because of the gangrene. My father told him that she was in her 90’s. What was the point? She wasn’t going to learn to function with a prosthetic. She’d be bedridden and miserable for the rest of her life. Just keep her comfortable. No surgery. No extraordinary measures. Give her something for the pain. And let her go quietly and with some dignity.

“No,” the doctor said. “She has to have the surgery.”

I watched as this went back and forth for at least 20 minutes as the doctor beat up on my father, almost accusing him of murder. Finally, in desperation, my father asked the doctor, “What would you do if it were your mother?”

Without skipping a beat, the doctor replied, “Exactly what you’re doing.”

“So why did you put me through the ringer for the last half hour trying to convince me to do something you wouldn’t do?”

“Hospital policy,” the doctor replied.

Act 3

Two days later, we arrived for another visit only to learn that my grandmother had suffered a major heart attack during the night, and that they had exercised a code blue and used extraordinary measures to bring her back from the dead — breaking three of her ribs in the process.

Two days later, we arrived for another visit only to learn that my grandmother had suffered a major heart attack during the night, and that they had exercised a code blue and used extraordinary measures to bring her back from the dead — breaking three of her ribs in the process.

“Why would you do that,” my father implored?

“Code blue was on her charts,” they responded.

“We didn’t ask for that. I told you we didn’t want that. Why did you do that? Take it off. No extraordinary measures, please. Do not resuscitate if her heart stops again. Just keep her comfortable. Keep her pain free. Don’t break anymore ribs bringing her back from the dead.”

Act 4

At this point, I had to return to school. But I was able to see my grandmother again a number of times after that as she was transferred to a special care facility, where she lingered for close to another year, never returning home, never leaving her bed ‘til the day she died. She was miserable and complained bitterly. It was not a good way to go. It was not kind. There was no dignity in it.

Act 5

While it’s true that my interests were already starting to drift away from a career in medicine–and more towards alternative treatments–before this incident, the experience with my grandmother finalized my decision. I realized that Hippocrates was onto something when he said, “First do no harm.” And a career in medicine was not conducive to its practice.

Doctors Vote Against Their Own Treatments

Now back to the report.

Although over a decade old and largely forgotten, the report recently resurfaced, appearing in a blog, a radio show, and referenced in several articles…and it’s even more damning on second reading. The report, published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, was actually the result of a survey designed to assess whether older physicians (mean age 68) discussed their preferences for medical care at the end of life with their physicians, whether they established advance directives, and what life-sustaining treatment they wished in the event of incapacity to make these decisions for themselves.2 Gallo JJ, Straton JB, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, Sulmasy DP, Wang NY, Ford DE. “Life-sustaining treatments: what do physicians want and do they express their wishes to others?” J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 Jul;51(7):961-9. http://www.readcube.com/articles/10.1046%2Fj.1365-2389.2003.51309.x?r3_referer=wol

Questionnaires were sent out to known surviving physicians of the Precursors Study, an on-going study that began in 1946, asking physicians about their preferences for life-sustaining treatments. Of 999 physicians who were sent the survey, 765 responded. Forty-six percent of the physicians felt that their own doctors were unaware of their treatment preferences or were not sure. And of these respondents, 59% had no intention of discussing their wishes with their doctors within the next year. In contrast, 89% thought their families were probably or definitely aware of their preferences. Sixty-four percent reported that they had established an advance directive. Compared to physicians without advance directives, physicians who established an advance directive were more likely to refuse treatments than those without advance directives.

Curiously, the researchers themselves thought the most important conclusion of the study was that, “This survey of physicians calls attention to the gap between preferences for medical care at the end of life and expressing wishes to others through discussion and advance directives, even among physicians.” For doctors themselves, that may indeed be the most important conclusion. For the rest of us, however, the most important conclusions can be read in the data where it talks about how many doctors would refuse end-of-life treatments–and specifically, which treatments they would refuse.

Curiously, the researchers themselves thought the most important conclusion of the study was that, “This survey of physicians calls attention to the gap between preferences for medical care at the end of life and expressing wishes to others through discussion and advance directives, even among physicians.” For doctors themselves, that may indeed be the most important conclusion. For the rest of us, however, the most important conclusions can be read in the data where it talks about how many doctors would refuse end-of-life treatments–and specifically, which treatments they would refuse.

As I learned from my grandmother’s situation, doctors will do anything to keep their patients alive, but when it comes to their own lives, or those of their loved ones, they often take a different approach. Knowing the pain associated with many treatments, and the limited effectiveness of those same treatments, it would seem that a majority of physicians choose not to take their cue from Dylan Thomas and, instead, opt to “Go gentle into that good night.”3 Dylan Thomas. “Do not go gentle into that good night.” Poets.org (Accessed 17 April 2014.) http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/15377

And again, based on my grandmother’s experience, they might just be onto something.

Incidentally, everyone keeps reversing the Dylan Thomas quote. The opening lines of his eponymous poem read:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Then again, I don’t think Thomas was actually talking about end-of-life medical treatments.

Certainly things have changed over the last decade. Chemotherapy, for example, is getting better–fewer side effects, more positive results (although it is still an iffy call at best). And yet, most doctors would still refuse it. As Dr. Ken Murray, the Clinical Assistant Professor of Family Medicine at USC, wrote in 2011, “Of course, doctors don’t want to die; they want to live. But they know enough about modern medicine to know its limits. And they know enough about death to know what all people fear most: dying in pain, and dying alone. They’ve talked about this with their families. They want to be sure, when the time comes, that no heroic measures will happen–that they will never experience, during their last moments on earth, someone breaking their ribs in an attempt to resuscitate them with CPR (that’s what happens if CPR is done right).”4 Ken Murray. “How Doctors Die: It’s Not Like the Rest of Us, But It Should Be.” Zocalo Public Square. November 30, 2011. (Accessed 17 April 2014.) http://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/2011/11/30/how-doctors-die/ideas/nexus/

See, and you probably thought I was exaggerating when I talked about my grandmother’s broken ribs from her Code Blue CPR.

As Dr. Murray says at the end of his article, “If there is a state of the art of end-of-life care, it is this: death with dignity. As for me, my physician has my choices. They were easy to make, as they are for most physicians. There will be no heroics, and I will go gentle into that good night. Like my mentor Charlie. Like my cousin Torch. Like my fellow doctors.”

Again with the Dylan Thomas anti-quote? (And if you’re getting the sense that Thomas’ poem looms large in this discussion, you would be correct.) Also, as I read Dr. Murray’s line about death with dignity, I couldn’t help but be reminded of Gene Kelly’s hysterical line from Singin in the Rain, “Dignity, always dignity.” 5 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9MhfKRiyvk4 )

Doctors Opt Out of Medical Intervention

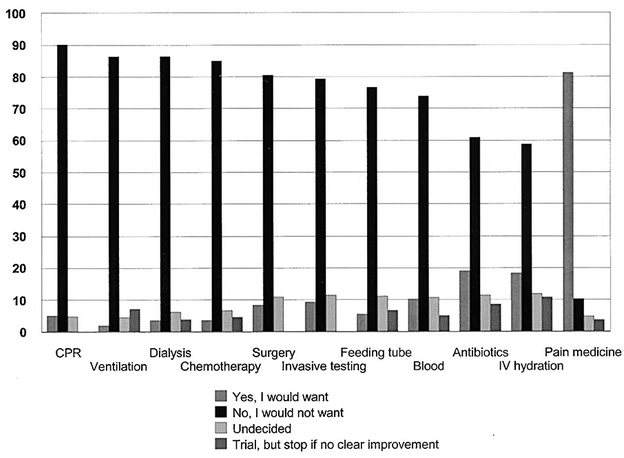

Now is probably a good time to take a look at the key chart from the report. It clearly shows how most doctors would turn down most major end-of-life medical interventions–and which interventions they like the least when it comes to their own health, understanding that they would still press you to use them if they were your doctor.

The top four are CPR, ventilation, dialysis, and chemotherapy. Amazingly, the only one likely to see any improvement if a new survey were conducted today is chemotherapy. As I mentioned earlier, chemo has become more refined over the years, less brutal on the body (but still not a lot of fun) and somewhat (although not necessarily dramatically) more effective for many cancers. But CPR is relatively unchanged. And keep in mind, we’re still talking about the rib breaking, bring ‘em back from the dead kind of CPR they did on my grandmother so she could vegetate for an extra year in a hospital bed. Ventilators are still pretty much the same–mechanical breathing devices that force your lungs to keep working when they no longer want to work on their own. And dialysis keeps you going when your kidneys have shut down. Unless you’re looking at a kidney transplant, which you’re not in an end-of-life scenario, you’re merely holding at bay what would be over in a few days without the dialysis.6 “Should I stop kidney dialysis?” WebMD. (Accessed 18 April 2014.) http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/should-i-stop-kidney-dialysis

Again, it’s crucial to remember that we’re talking about end-of-life interventions that merely drag out the inevitable at the cost of great pain and suffering (like my grandmother), not life-saving interventions that might be more meaningful much earlier in the process. And thus, in the survey, doctors also overwhelming turned down, for themselves, surgery, invasive testing, feeding tubes, transfusions, antibiotics, and even IV hydration if all it did was postpone the inevitable. Why prolong the suffering and, in fact, increase your pain and discomfort, merely to drag out the inevitable? And thus, it probably comes as no surprise that the only intervention they overwhelmingly opted for was pain medication. How very human of them.

Conclusion

Doctors know the pain and suffering involved in all of these interventions and opt out of all of them in overwhelming numbers when it comes to end-of-life interventions for themselves. That’s worth taking note of. Nevertheless, they will press you and yours to opt for them when your time comes. This is key. They will press you to do what they would never do for themselves. Why? This is all speculation, but I would guess:

- Ego plays a role. When it comes to them personally, pain and suffering have top billing. But when it comes to you and yours as their patients, “winning at all costs” becomes the priority.

- Practice makes perfect. The more times they do a procedure, the better they get at it. Thus, practicing is an important part of honing their skill set. However, they’re much happier practicing on you as opposed to having another doctor practice on them.

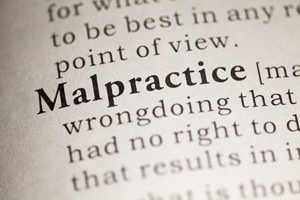

It’s hospital policy–to protect against malpractice suits. (And for this reason, we can thank ourselves…and the American Trial Lawyers Association.) A continuous barrage of frivolous lawsuits and outrageous jury awards has created this situation. For the hospital, it really is better to inflict massive amounts of pain and suffering on you, as it prevents you from being able to sue them. You see, as long as the hospital can prove they left no stone unturned in your end-of-life care, no matter how much pain and suffering it caused you, then there’s no room for your heirs to sue. Unfortunately, that’s not necessarily good for you.

It’s hospital policy–to protect against malpractice suits. (And for this reason, we can thank ourselves…and the American Trial Lawyers Association.) A continuous barrage of frivolous lawsuits and outrageous jury awards has created this situation. For the hospital, it really is better to inflict massive amounts of pain and suffering on you, as it prevents you from being able to sue them. You see, as long as the hospital can prove they left no stone unturned in your end-of-life care, no matter how much pain and suffering it caused you, then there’s no room for your heirs to sue. Unfortunately, that’s not necessarily good for you.- It’s also hospital policy because it dramatically increases billings. It has been said that 50% of all medical expenses are incurred in the last six months of life. That is most likely an exaggerated number, as I have been unable to find any valid studies to support it. However, I have seen many studies that have concluded that some 30% of all medical expenses occur in the last year of life…and that’s bad enough.7 Donald R Hoover, Stephen Crystal, Rizie Kumar, Usha Sambamoorti, and Joel C Cantor. “Medical Expenditures during the Last Year of Life: Findings from the 1992–1996 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey.” Health Serv Res. Dec 2002; 37(6): 1625–1642. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1464043/ How bad becomes clear when you look at those same numbers in another way. They can also be read as: one percent of the population accounts for 30 percent of the nation’s health care expenditures. Quite simply, no healthcare system based on those numbers can remain viable long term.

So what does this mean for us? What conclusions can we draw from this survey?

It means that when it comes to end-of-life care, you really do have a choice. If you know most doctors wouldn’t opt for a treatment, why would you? If you know that most doctors would turn it down, then it makes it easy for you to turn it down when doctors and the hospitals start ramping up the pressure.

And it gives you one more reason to turn to alternative treatments when it comes to terminal illness. Whether or not it can save you–and many people really are saved by alternative treatments after conventional treatments have failed–but more importantly, even if you do die after opting for an alternative treatment, you tend to die feeling a whole lot better. Which scenario sounds better to you?

- Chemotherapy for late stage cancer with virtually no chance of success that carries with it violent nausea, loss of hair, and loss of all taste for food…and then dying?

- Or cleaning out the toxins in your body. Eating natural fresh foods and using some supplements that boost your immune system or directly address your illness…and then dying.

Under which scenario do you think you feel better when you die? Under which scenario do you think you get to enjoy more quality time with your family before you die? Under which scenario do you think you are more likely to die at home surrounded by family, rather than alone in a hospital room, surrounded by strangers and an unfriendly environment?

I know which way my grandmother would answer.

And if it’s impossible for you to die at home, and you still want to avoid the hospital, there’s always hospice. It’s not home, but it’s a whole lot more dignified than becoming an experimental guinea pig in a hospital.

Let me finish with a movie clip featuring Albert Brooks playing the role of Dr. Butz (yes, you read that correctly) in the movie Critical Care, starring baby James Spader (yes, we all are young once). It’s really quite brilliant. It sums up everything we’ve talked about today and is bitingly funny at the same time. Oh, and it gives us one more chance to riff on Dylan Thomas. Enjoy

References

| ↑1 | “Judge orders chemotherapy for 13-year-old cancer patient.” CNN.com/US May 26, 2009. (Accessed 18 April 2014.) http://www.cnn.com/2009/US/05/26/minnesota.forced.chemo/index.html |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gallo JJ, Straton JB, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, Sulmasy DP, Wang NY, Ford DE. “Life-sustaining treatments: what do physicians want and do they express their wishes to others?” J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 Jul;51(7):961-9. http://www.readcube.com/articles/10.1046%2Fj.1365-2389.2003.51309.x?r3_referer=wol |

| ↑3 | Dylan Thomas. “Do not go gentle into that good night.” Poets.org (Accessed 17 April 2014.) http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/15377 |

| ↑4 | Ken Murray. “How Doctors Die: It’s Not Like the Rest of Us, But It Should Be.” Zocalo Public Square. November 30, 2011. (Accessed 17 April 2014.) http://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/2011/11/30/how-doctors-die/ideas/nexus/ |

| ↑5 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9MhfKRiyvk4 |

| ↑6 | “Should I stop kidney dialysis?” WebMD. (Accessed 18 April 2014.) http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/should-i-stop-kidney-dialysis |

| ↑7 | Donald R Hoover, Stephen Crystal, Rizie Kumar, Usha Sambamoorti, and Joel C Cantor. “Medical Expenditures during the Last Year of Life: Findings from the 1992–1996 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey.” Health Serv Res. Dec 2002; 37(6): 1625–1642. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1464043/ |

“As I have no resources to

“As I have no resources to develop my tools,

I take all your comments and criticism as it

show a better way for its development’

There is nothing to comment on this”

With Regards

-bhaskar

thanks for the excellent

thanks for the excellent report. but I cannot understand your videos. I am deaf and I cannot hear. Your videos are not captioned.

Please consider. Thank you.

Andi

How timely is this article

How timely is this article for me Jon!

Until recently, I thought I was invincible. I am 65 and thought I was in pretty good health. However, recent lab tests may prove differently. I have changed doctors and will see a new MD tomorrow. I don’t know what these tests will ultimately mean, but I have been thinking and praying about how I will deal with any bad news. I have long told my family that I do not want any extraordinary measures and have an advanced directive that I will give to the doctor. This article just confirms my belief and gives me confidence to pursue alternative measures first.

Thank you for all you do to help those of us who often feel we are out here alone.

Hi Jon.

Hi Jon.

Thank you for yet another article depicting your thoughts.

You are getting closer to where I have been for a long time.

The established medicine needs to be discarded in favor of a more humane paradigm, which was “born” in 1981, no less.

In addition to said paradigm, there are very capable people, that have, just like you, gone a different path, but based on the aforesaid paradigm. They have realized, that we are not just a collection of cells, who in turn are comprised of bacteria, but very precious examples of Nature’s Biology. Poisons are counter indicated in any case, but most particularly, when Mother Nature is already busy healing. Why is it, that humans think they know better than Nature how to sustain life? Learninggnm.com.