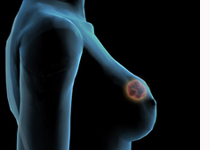

Alcohol and health. Good for you, bad for you. Back and forth the debate rages. Some studies indicate that moderate drinking improves health and extends life (particularly in terms of heart health), whereas other studies indicate it may be implicated in an increased risk of breast cancer for women — one of the leading causes of cancer death in women around the world. In recent years, there’s been some focus on what women can do to decrease their risk of breast cancer — such as breastfeeding and eating a good diet. But one thing they’ve been consistently urged to do is stop drinking alcohol. And now new studies may reinforce that conclusion, while at the same time helping shed some light on exactly how alcohol affects the body and raises the risk of breast cancer.

According to findings presented last week at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, in San Diego, alcohol, consumed even in small amounts, may significantly increase the risk of breast cancer — particularly estrogen-receptor/progesterone-receptor positive breast cancer. Further, the findings are supported by a second study that found an association between breast cancer risk and two genes involved in alcohol metabolism.

Alcohol and estrogen/progesterone receptor based breast cancers

The first study followed more than 184,000 postmenopausal women for an average of seven years. Those who had less than one drink a day had a 7 percent increased risk of breast cancer compared to those who did not drink at all. Women who drank one to two drinks a day had a 32 percent increased risk, and those who had three or more glasses of alcohol a day had up to a 51 percent increased risk. The risk was seen mostly in those 70 percent of tumors classified as estrogen receptor- and progesterone receptor-positive. The researchers suspect that alcohol may have an effect on breast cancer via an effect on estrogen in the body.

The first study followed more than 184,000 postmenopausal women for an average of seven years. Those who had less than one drink a day had a 7 percent increased risk of breast cancer compared to those who did not drink at all. Women who drank one to two drinks a day had a 32 percent increased risk, and those who had three or more glasses of alcohol a day had up to a 51 percent increased risk. The risk was seen mostly in those 70 percent of tumors classified as estrogen receptor- and progesterone receptor-positive. The researchers suspect that alcohol may have an effect on breast cancer via an effect on estrogen in the body.

The risk was similar whether women consumed beer, wine, or hard liquor. Alcohol consumption in any form was the common denominator. What the exact mechanism is that might lead to this increase in cancer is not known. It is suspected that in some forms of breast cancer, malignant cells have receptors that render them sensitive to hormones such as estrogen. These tumors re referred to by doctors as being estrogen-receptor/progesterone-receptor positive (ER+/PR+) breast cancers.

And in fact the study found that alcohol specifically increased the risk most for ER+/PR+ tumors — the most common type of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. In normal circumstances, when women reach menopause, levels of both estrogen and progesterone in their bodies fall precipitously, which, according to the medical establishment, should lead to fewer of these tumors. But the study found that post-menopausal women actually had higher rates of these hormone-responsive tumors if they drank alcohol. And the more they drank, the higher the risk. As I stated earlier, the study found that drinking less than one serving of alcohol a day still resulted in a 7% increase of risk for the ER+/PR+ types of breast cancer. And drinking as much as three servings of alcohol per day vaulted your risk upwards to 51%.

It is important to note that in women with estrogen-receptor negative, progesterone-receptor negative (ER-/PR-) tumors, there appeared to be no link between drinking and breast cancer.

The question of course arises, “Why would drinking alcohol raise the risk of hormone-fueled tumors regardless of receptor sites?” As I mentioned earlier, the answer seems to be that alcohol interferes with estrogen metabolism, which in turnincreases the risk of hormone-sensitive breast cancer. We will talk more about this later,but for now, let’s take a look at the second study I mentioned.

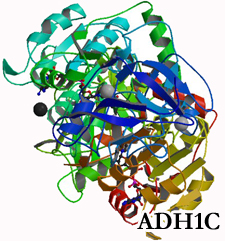

Alcohol and ADH1B and ADH1C gene variant breast cancer

A second study, also presented in San Diego, explored another possible mechanism by which alcohol consumption increases breast cancer risk. “For years, we’ve known that there’s an association between alcohol drinking and breast cancer risk,but nobody knows yet what the underlying biological mechanisms are,” said Dr. Catalin Marian,lead author of the study and a research instructor in oncology at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. “The logical step was to begin analyzing the alcohol metabolizing genes.”

A second study, also presented in San Diego, explored another possible mechanism by which alcohol consumption increases breast cancer risk. “For years, we’ve known that there’s an association between alcohol drinking and breast cancer risk,but nobody knows yet what the underlying biological mechanisms are,” said Dr. Catalin Marian,lead author of the study and a research instructor in oncology at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. “The logical step was to begin analyzing the alcohol metabolizing genes.”

The researchers studied DNA samples from 991 women with breast cancer and 1,698 women without cancer. They found that variants in two of these genes, ADH1B and ADH1C, were associated with a two-fold increase in breast cancer risk. But the study did not prove a definite cause-and-effect link. “This is an association,” Dr. Marian said. “This type of study is good for generating hypotheses. It’s not a definite conclusion. It needs to be replicated by other studies to say for sure that what we found is there.”

Putting the alcohol breast cancer studies in perspective

While the studies do not prove cause and effect, they lend plausibility to growing evidence implicating drinking as a risk factor for breast cancer, says Elizabeth Platz, ScD, a specialist in cancer prevention at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “The beauty of the research is that it tells us something about the mechanisms” by which alcohol may raise breast cancer risks.

Another researcher urged caution in interpreting the results of both studies.

“These studies are too early for use in a clinical setting or to advance a public health message,” said Dr. Peter Shields, co-author of the genetics study and deputy director of the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

To better understand what this message might or should be, let’s explore the alcohol/estrogen metabolism question that I mentioned earlier. For it is here that we have the most to learn — and the most to be confused about.

Alcohol and estrogen utilization

Physiologically, the higher the estrogen levels in your body, the more readily alcohol is absorbed — but the more slowly it is broken down. But the problem is compounded by the fact that the very act of drinking alcohol actually increases estrogen levels, almost tripling levels in post-menopausal women in a matter of minutes. As a result, after you drink, you get spurts of estrogen that can be as high as 300 percent higher within 30 minutes of consumption. In other words, it’s one thing to have a constant amount of estrogen and occasionally have a rise before you ovulate. But if you get these rises in estrogen every time you have a drink, and for years past your ability to ovulate, this would quite likely be a significant breast cancer risk. The bottom line is that we know that estrogen levels increase after you drink. Andwe know that estrogen is linked to breast cancer. Therefore, it should be no surprise that estrogen is linked to breast cancer more often when women drink.

The progesterone/cancer question

Researchers love to lump (no pun intended) estrogen and progesterone receptors together when talking about breast cancer. But they are not the same by any stretch of the imagination, and the action of estrogens and progesterone when it comes to breast cancer are worlds apart. For that matter, you can’t even lump all estrogens together. Estrone and estradiol are cancer promoting, whereas estriol may be cancer protective. And then, of course there are the synthetic estrogens and progesterones and the petroleum based xenoestrogens — potent and cancer promoting in amounts as low as a billionth of a gram. In the world of hormones and breast cancer, these differences are not subtle; they are fundamental.

The connection between estrogen, and breast cancer (with alcohol an added catalyst) is all but proven, but what about the connection between progesterone and cancer? After all, much of the cancer risk referred to above is associated with those 70 percent of tumors classified as estrogen-receptor/progesterone receptor-positive.

The connection between estrogen, and breast cancer (with alcohol an added catalyst) is all but proven, but what about the connection between progesterone and cancer? After all, much of the cancer risk referred to above is associated with those 70 percent of tumors classified as estrogen-receptor/progesterone receptor-positive.

Progesterone is an ovarian steroid hormone that is essential for normal breast development during puberty and in preparation for lactation and breastfeeding. The actions of progesterone are primarily mediated by its high-affinity receptors, which include the (PR)-A receptor and its -B isoforms, which are located in tissue throughout the body, including the brain, where progesterone controls reproductive behavior, the reproductive organs, and of course the breasts.

As I said earlier, the role of estrogen as a potent breast mitogen (a substance that triggers cell division) is undisputed, and inhibitors of the estrogen receptor and estrogen-producing enzymes (aromatases) are now recognized as effective first-line cancer therapies. However, progesterone receptor action in breast cancer has barely been studied, and the results of those studies are ambiguous at best — and, in fact, when a connection is found at all, it is associated with the use of progestins (synthetic progesterones), not natural or bio-identical progesterones.

Progestins are frequently prescribed for contraception or during postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy, in which the progestins are combined with synthetic estrogens as a means to block estrogen-induced endometrial growth. As I have said, the role of estrogen as a potent breastmitogen is undisputed, and inhibitors of the estrogen receptor and estrogen-producing enzymes (aromatases) are effective first-line cancer therapies. But there is no evidence of any note that indicates that natural progesterone is connected to an increased incidence of breast cancer. In point of fact, most evidence indicates that it is breast cancer inhibitory.

Conclusion: drinking and breast cancer

Conclusion: drinking and breast cancer

So what does it all mean?

- Well, first and foremost, if breast cancer runs in your family, you may want to think twice about drinking.

- Drinking aside, the key issue here is the cancer promoting qualities of estrogen — and therefore, we have yet another reason to be concerned about estrogen dominance.

- And finally, if you do decide to drink, you might want to consider using a natural progesterone crème to buffer the effects of massive estrogen spurts your body is likely to experience.

PS, bilateral prophylactic mastectomy

And now a related, but tangential, issue.

The connection between alcohol and breast cancer gives us yet another reason to reconsider the advisability of prophylactic breast mastectomies to reduce the risk of breast cancer. As I discussed in a 2006 blog entry, the BRCA gene mutation that is prompting ever increasing numbers of women to remove their breasts as a cancer preventative, is hardly a guarantor of breast cancer…without a corresponding family history of breast cancer. In fact, without the family history, your risk of getting breast cancer is the same as if you didn’t have the gene mutation at all. But family history is open to interpretation. It doesn’t necessarily mean genetic inevitability. Living on a farm, for example, can increase your risk fourfold. In other words, just moving from the farm might be all that’s required to drop your risk to normal and save your breasts. And now we see that for some women, merely cutting out drinking might dramatically reduce your risks. If you have the BRCA mutation, but come froma family that drinks regularly and has a history of breast cancer, then just by stopping drinking you might completely negate the BRCA gene bump — particularly since some studies indicate that alcohol directly affects the BRCA1 gene. In other words, becoming a teetotaler might be an alternative to lopping off your breasts. Look, prophylactic breast mastectomy has always been hard to justify; the latest studies on alcohol and breast cancer just make it that much harder.