A study published several months ago in Genome Medicine found a lack of evidence for an impact from supplemental probiotics on fecal microbiota composition in healthy adults.1 Nadja B. Kristensen, Thomas Bryrup, Kristine H. Allin, et al. “Alterations in fecal microbiota composition by probiotic supplementation in healthy adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials.” Genome Medicine 20168:52. 10 May 2016. http://genomemedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13073-016-0300-5 Not surprisingly, the mainstream media was all over it, declaring probiotic supplements a waste of money.

Probiotic foods now represent $1.3 billion in annual sales and are expected to grow about 15% a year.

Make no mistake, whereas once there were only a handful of us in the alternative health community promoting the value of eating probiotic foods and probiotic supplementation, it has now gone mainstream with even hospitals and medical doctors recommending their use, and they have been added to everything from probiotic water2 http://www.sujajuice.com/product-category/pressed-probiotic-waters/ to probiotic cookies3 http://ikuky.com/index.php to probiotic gum.4 http://culturedcare.com/ In fact, forget capsules, probiotic foods alone now represent $1.3 billion in annual sales and are expected to grow about 15% a year for the foreseeable future. This is no accident; food companies have spent the last several years adding probiotics to every food they can think of and spending millions and millions of dollars promoting the heck out of them.

To be sure, although there is substantial evidence that gut bacteria are responsible to a large degree for the state of your health, the evidence in support of the value of many of these products is a bit spotty. In the words of the National Institutes of Health: the benefits of probiotic foods and supplements “have not been conclusively demonstrated.”5 “Probiotics: In Depth.” NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Date Created: January 2007. Last Updated: October 2016. http://nccih.nih.gov/health/probiotics/introduction.htm

So, what’s the story? Is the NIH correct? Does this recent study put the nail in the coffin for probiotic supplements as the mainstream media would have us believe? Or is it all the usual nonsense? In fact, the study is probably quite accurate in its observations within the confines of its limitations, but woefully inaccurate in the conclusions it draws from those observations.

Let’s begin by taking a closer look at the study.

Alterations in fecal microbiota composition by probiotic supplementation in healthy adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials

Well, the title of the study itself gives you a clue as to its first limitation. The data wasn’t personally gathered and controlled by the researchers involved in the study. It is, as the title says, a systematic review of other researchers’ randomized controlled trials. In fact, the study was conducted at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen and is a review of seven earlier randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effect of probiotic products on the fecal microbiota of healthy adults.6 Lahti L, Salonen A, Kekkonen RA, Salojärvi J, Jalanka-Tuovinen J, Palva A, et al. “Associations between the human intestinal microbiota, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and serum lipids indicated by integrated analysis of high-throughput profiling data.” PeerJ. 2013;1:e32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3628737/ , 7 Rampelli S, Candela M, Severgnini M, Biagi E, Turroni S, Roselli M, et al. “A probiotics-containing biscuit modulates the intestinal microbiota in the elderly.” J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(2):166–72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23364497 , 8 Ferrario C, Taverniti V, Milani C, Fiore W, Laureati M, De Noni I, et al. “Modulation of fecal Clostridiales bacteria and butyrate by probiotic intervention with Lactobacillus paracasei DG varies among healthy adults.” J Nutr. 2014;144(11):1787–96. http://jn.nutrition.org/content/early/2014/09/03/jn.114.197723 , 9 Bjerg AT, Sørensen MB, Krych L, Hansen LH, Astrup A, Kristensen M, et al. “The effect of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei L. casei W8® on blood levels of triacylglycerol is independent of colonisation.” Benef Microbes. 2015;6(3):263–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25273547 , 10 Brahe LK, Le Chatelier E, Prifti E, Pons N, Kennedy S, Blædel T, et al. “Dietary modulation of the gut microbiota–a randomised controlled trial in obese postmenopausal women.” Br J Nutr. 2015;114(03):406–17. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4531470/ , 11 Hanifi A, Culpepper T, Mai V, Anand A, Ford A, Ukhanova M, et al. “Evaluation of Bacillus subtilis R0179 on gastrointestinal viability and general wellness: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in healthy adults.” Benef microbes. 2014;6(1):19–27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25062611 , 12 Simon MC, Strassburger K, Nowotny B, Kolb H, Nowotny P, Burkart V, et al. “Intake of Lactobacillus reuteri improves incretin and insulin secretion in glucose-tolerant humans: a proof of concept.” Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1827–34. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26084343

Well, the title of the study itself gives you a clue as to its first limitation. The data wasn’t personally gathered and controlled by the researchers involved in the study. It is, as the title says, a systematic review of other researchers’ randomized controlled trials. In fact, the study was conducted at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen and is a review of seven earlier randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effect of probiotic products on the fecal microbiota of healthy adults.6 Lahti L, Salonen A, Kekkonen RA, Salojärvi J, Jalanka-Tuovinen J, Palva A, et al. “Associations between the human intestinal microbiota, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and serum lipids indicated by integrated analysis of high-throughput profiling data.” PeerJ. 2013;1:e32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3628737/ , 7 Rampelli S, Candela M, Severgnini M, Biagi E, Turroni S, Roselli M, et al. “A probiotics-containing biscuit modulates the intestinal microbiota in the elderly.” J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(2):166–72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23364497 , 8 Ferrario C, Taverniti V, Milani C, Fiore W, Laureati M, De Noni I, et al. “Modulation of fecal Clostridiales bacteria and butyrate by probiotic intervention with Lactobacillus paracasei DG varies among healthy adults.” J Nutr. 2014;144(11):1787–96. http://jn.nutrition.org/content/early/2014/09/03/jn.114.197723 , 9 Bjerg AT, Sørensen MB, Krych L, Hansen LH, Astrup A, Kristensen M, et al. “The effect of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei L. casei W8® on blood levels of triacylglycerol is independent of colonisation.” Benef Microbes. 2015;6(3):263–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25273547 , 10 Brahe LK, Le Chatelier E, Prifti E, Pons N, Kennedy S, Blædel T, et al. “Dietary modulation of the gut microbiota–a randomised controlled trial in obese postmenopausal women.” Br J Nutr. 2015;114(03):406–17. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4531470/ , 11 Hanifi A, Culpepper T, Mai V, Anand A, Ford A, Ukhanova M, et al. “Evaluation of Bacillus subtilis R0179 on gastrointestinal viability and general wellness: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in healthy adults.” Benef microbes. 2014;6(1):19–27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25062611 , 12 Simon MC, Strassburger K, Nowotny B, Kolb H, Nowotny P, Burkart V, et al. “Intake of Lactobacillus reuteri improves incretin and insulin secretion in glucose-tolerant humans: a proof of concept.” Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1827–34. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26084343

For the current study, the success or failure of supplementation was determined by how much the beneficial bacteria of each of the subjects in the seven RCTs was changed by that supplementation–not necessarily by any changes in their health.

Studies were included based on study population (healthy adults), study design (RCT), means of intervention (probiotics or placebo), and intervention outcome (changes in the composition of the fecal microbiota). Studies were excluded if they were not RCTs, if they examined only effects within one group of individuals without comparing them to another, if they combined probiotics with other interventions, or if they examined both healthy and unhealthy individuals.

Study participants across the seven original RCTs included in the review were healthy adults between 19 and 88 years of age. Notably, the numbers of individuals involved in the seven studies ranged from as few as 21 to at most 81. Probiotic supplements were administered as biscuits, milk-based drinks, sachets, or capsules for periods of 21 to 42 days.

Again, the researchers investigated the seven original studies for any reported effects of the probiotics on the overall structure of the fecal microbiota in the test subjects, including the number of species present, the evenness (distribution of species within the populations) and whether the probiotics groups of study participants, as a result of the intervention, had different changes in bacteria living in their gut than the placebo groups. And as already stated, any changes in health outcomes were not considered.

The authors found that of the seven original RCTs included in the study, only one observed significantly greater changes in the bacterial species composition of the fecal microbiota in individuals who consumed probiotics compared to those who did not. As Nadja Buus Kristensen, a junior author of the study, said, “A systematic review of experimental evidence allows us to pull together evidence and look at the relationship between probiotic products and the composition of the fecal microbiota in healthy people using explicit, systematic methods, ensuring the highest level of evidence.” She then went on to say, “According to our systematic review, no convincing evidence exists for consistent effects of examined probiotics on fecal microbiota composition in healthy adults, despite probiotic products being consumed to a large extent by the general population.”

Again, health outcomes aside, the researchers did acknowledge that there is evidence to suggest that probiotic supplementation can be helpful in rebalancing intestinal cultures when a state of dysbiosis exists as might be caused by obesity, diabetes, or colorectal cancer. As Oluf Pedersen, professor at the University of Copenhagen and senior author of the paper said, “While there is some evidence from previous reviews that probiotic interventions may benefit those with disease-associated imbalances of the gut microbiota, there is little evidence of an effect in healthy individuals. To explore the potential of probiotics to contribute to disease prevention in healthy people, there is a major need for much larger, carefully designed and carefully conducted clinical trials. These should include ideal composition and dosage of known and newly developed probiotics combined with specified dietary advice, optimal trial duration and relevant monitoring of host health status.”

When all was said and done, however, as the study concluded, there is little evidence of an effect in healthy individuals unless they are in a state of dysbiosis–suffering from an imbalance of proper intestinal flora.

Ouch!

Issues with the Study

To be sure, the study itself identified a number of concerns about its own validity. The authors noted that the small sample sizes of the RCTs, the variation in susceptibility to the probiotics between individual participants, and the use of different probiotic strains (either in isolation or in combination), not to mention the variations between the diets of individuals included in various study groups may have masked the true impact of probiotic intake. But that just scratches the surface when it comes to evaluating the study’s validity.

In fact, the results of the seven RCTs were hardly as negative as this review implies. For example:

- The RCT using biscuits laced with Bifidobacterium longum and L heveticus found that just one-month consumption was effective in redressing some of the age-related dysbioses of the intestinal microbiota. In particular, the probiotic treatment reverted the age-related increase of the opportunistic pathogens Clostridium cluster XI, Clostridium difficile, Clostridium perfringens, Enterococcus faecium and the enteropathogenic genus Campylobacter.13 Rampelli

- One of the Danish studies was specifically designed to see if supplementation with L. casei helped with blood levels of triglycerides. It was deemed a failure because it did not and it supposedly did not change the composition of the fecal microbiota. On that other hand, according to the study itself, it did result in an increase in the presence of L. casei in the gut. And even two weeks after supplementation ended, the relative abundance of the L. casei group was still increased 14 times compared to before the intervention.14 Bjerg The problem is that L. casei isn’t known for controlling triglyceride levels. On the other hand, L. casei is one of the best documented and most studied probiotics that can aid in overall digestive and immune system health.15 Harbige LS, Pinto E, Allgrove J, Thomas LV. “Immune response of healthy adults to the ingested probiotic Lactobacillus casei Shirota.” Scand J Immunol. 2016 Oct 8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27718254 It has been reported to inhibit the growth of unhealthy bacteria in the intestinal tract, help reduce symptoms of lactose intolerance,16 Almeida CC, Lorena SL, Pavan CR, Akasaka HM, Mesquita MA. “Beneficial effects of long-term consumption of a probiotic combination of Lactobacillus casei Shirota and Bifidobacterium breve Yakult may persist after suspension of therapy in lactose-intolerant patients.” Nutr Clin Pract. 2012 Apr;27(2):247-51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22402407 control diarrhea, enhance immune responses and to decrease the risk for bladder cancer. So, the fact that it didn’t lower triglyceride levels doesn’t mean that it is a waste of money. It’s a bit like criticizing Tom Brady because he’s not a good tennis player. Evaluate him for what he’s good at–football–and you come to a different conclusion.

- Yet another one of the RCTs found that enrichment of gut microbiota with L. reuteri increases insulin secretion, possibly due to augmented incretin release.17 Simon Again, no change in the fecal microbiota, but hardly a failure. Which brings to the major hole in the current study.

The Giant, Giant, Giant Hole in the Study

One of the RCTs examined supplementation with L. rhamnosus. The current review considered it a failure for probiotics since the RCT concluded that “Based on a high-resolution microbiota analysis, intake of L. rhamnosus GG did not modify the composition of the intestinal ecosystem in healthy adults…” However, to consider rhamnosus supplementation a failure, you have to ignore the rest of the sentence, “…indicating that probiotics confer their health effects by other mechanisms.”

One of the RCTs examined supplementation with L. rhamnosus. The current review considered it a failure for probiotics since the RCT concluded that “Based on a high-resolution microbiota analysis, intake of L. rhamnosus GG did not modify the composition of the intestinal ecosystem in healthy adults…” However, to consider rhamnosus supplementation a failure, you have to ignore the rest of the sentence, “…indicating that probiotics confer their health effects by other mechanisms.”

And here’s the crux of the issue. The current study determined the success or failure of probiotic supplementation according to one primary criterion: did the supplementation recorded in the seven RCTs significantly change the bacterial species composition of the fecal microbiota in individuals who consumed probiotics compared to those who did not. In a moment, I’ll explain why that criterion is meaningless. But first, let’s talk about some of the peer reviewed “health effects” conferred by L. rhamnosus.

Supplementation with L. rhamnosus has been shown to help everything from improving fat metabolism18 Zhang Z, Zhou Z, Li Y, et al. “Isolated exopolysaccharides from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG alleviated adipogenesis mediated by TLR2 in mice.” Sci Rep. 2016 Oct 27;6:36083. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27786292 to relieving IBS,19 Currò D, Ianiro G, Pecere S, et al. “Probiotics, fibre and herbal medicinal products for functional and inflammatory bowel disorders.” Br J Pharmacol. 2016 Oct 3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27696378 and from ameliorating Candida20 Oliveira VM, Santos SS, Silva CR, Jorge AO, Leão MV. “Lactobacillus is able to alter the virulence and the sensitivity profile of Candida albicans.” J Appl Microbiol. 2016 Sep 8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27606962 to improving intestinal permeability and modulating the inflammatory response in the spleen and colon.21 Khailova L, Baird CH, Rush AA, et al. “Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment improves intestinal permeability and modulates inflammatory response and homeostasis of spleen and colon in experimental model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia.” Clin Nutr. 2016 Oct 1. pii: S0261-5614(16)31265-1. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27745813 Not bad for something that’s supposedly a complete waste of money.

So how can this happen if supplementation is not presenting any changes in the fecal microbiota? And the answer is remarkably simple. While it is true that in healthy individuals there is a heavy concentration of beneficial bacteria in the colon, that is not the only place that bacteria colonize in the intestinal tract. In fact, beneficial bacteria colonies can be found all along the intestinal tract, from mouth to anus. In your mouth alone, it is estimated that there are over 100 million bacteria in every milliliter of saliva from more than 600 different species. The important thing to understand is that different species of beneficial bacteria colonize different areas of the intestinal tract. For example, the colon and fecal matter are the province of different strains of bifidobacteria. Most of the lactobacillus bacteria such as acidophilus and rhamnosus prefer the small intestine.22 Ogita T, Bergamo P, Maurano F, et al. “Modulatory activity of Lactobacillus rhamnosus OLL2838 in a mouse model of intestinal immunopathology.” Immunobiology. 2015 Jun;220(6):701-10. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25623030 In other words, if you’re looking for changes from rhamnosus supplementation in the micobiota of the colon, you won’t find it because you’re looking in the wrong place.

This is a fairly significant flaw in the study!

Dysbiosis

Another major problem with the study concerns the issue of dysbiosis since the review concluded that supplementation would only be of value in cases of dysbiosis. But is dysbiosis really as uncommon as the study’s authors would have us believe? Is it only found in extreme circumstances? And the answer is probably not. To be sure, dysbiosis is definitely associated with disease as the authors state, but also with far more conditions than they acknowledge. Other conditions associated with reduced levels of beneficial bacteria in either the large or small intestine can include: acne, ADHD, allergies, arthritis, asthma, bladder and urinary-tract infections, breast pathologies, cardiac problems, chronic fatigue, colitis, colon cancer, compromised immunity, constipation, diarrhea, diverticulitis, ear and respiratory infections in children, eye, ear, nose and throat diseases, foul breath and body odor, gastritis, headaches, hormonal imbalances, IBS, liver and gallbladder problems, migraine headaches, ovarian and uterine cancers, PMS, sinus problems, spastic colon, stomach bloating, and vaginal yeast infections.

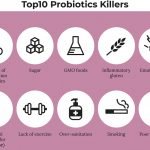

And that’s just the tail of the tapeworm. When you actually pull on the tail, you find there’s a whole lot more to the worm before you get to the head. Consider for a moment all of the non-disease conditions that can trigger dysbiosis. As we’ve discussed in previous newsletters:

Over time, the colonies of friendly bacteria just naturally age and lose their vitality. (Think of it like a royal family that eventually fizzles out after years of inbreeding.)

Over time, the colonies of friendly bacteria just naturally age and lose their vitality. (Think of it like a royal family that eventually fizzles out after years of inbreeding.)- Disruptions and changes in the acid/alkaline balance of the bowels can play a major role in reducing the growth of beneficial bacteria. In addition, these changes tend to favor the growth of harmful viral and fungal organisms as well as putrefactive, disease-causing bacteria.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) like Advil, Motrin, Midol, etc. are destructive to intestinal flora.

- Chlorine in the drinking water not only serves to kill bacteria in the water; it is equally devastating to the colonies of beneficial bacteria living in the intestines. The problem is that nature abhors a vacuum, and harmful bacteria then move in to occupy the abandoned “plots.”

- Radiation and chemotherapy are devastating to your inner bacterial environment.

- Virtually all meat, chicken, and dairy that you eat (other than organic) is loaded with antibiotics, which destroy all of the beneficial bacteria in your gastrointestinal tract.

- A diet high in meats and fats, because they take so long to break down in the human body, promotes the growth of the harmful, putrefying bacteria.

- Constipation, of course, allows harmful bacteria to hang around longer, which allows them to proliferate.

- Cigarettes, alcohol, and stress are also major culprits, as are some antibiotic herbs, such as goldenseal (if taken in sufficient quantity and/or used too frequently).

- And if you’ve ever been subjected to a round of “medicinal” antibiotics, you can kiss your beneficial bacteria goodbye. The problem is that antibiotics indiscriminately destroy both bad and good bacteria, allowing virulent, mutant strains of harmful microorganisms to emerge and run rampant inside the body. Antibiotics (both medicinal and in our food supply) are the number one culprit in the overgrowth of harmful pathogens in the gastrointestinal tract (a condition called dysbiosis).

The Benefits of Supplementing with a Good Probiotic Formula

To be sure, many of the so called probiotic foods and supplements being marketed today aren’t worth very much in terms of health. They contain either the wrong cultures or very few live cultures. They are not very useful. On the other hand, there can be no true health or recovery from disease unless you have colonies of over 100 trillion beneficial microorganisms flourishing in your intestinal tract, from your mouth to your anus, aiding in digestion, absorption, the production of significant amounts of vitamins and enzymes, and working to crowd out all harmful bacteria — allowing them no place to gain a foothold. SUPPLEMENTATION WITH A GOOD PROBIOTIC IS MANDATORY TO RAISE YOUR BASELINE OF HEALTH AND STRENGTHEN YOUR IMMUNE SYSTEM. The benefits of a probiotically optimized intestinal tract include:

- Lowered cholesterol

- Inhibition of cancer

- Protection against food poisoning

- Protection against stomach ulcers

- Protection against lactose intolerance and casein intolerance

- Enhanced immunity

- Protection against many harmful bacteria, viruses, and fungi

- Protection against candida overgrowth and vaginal yeast infections

- Prevention and correction of constipation and diarrhea, ileitis and colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, and a whole range of other digestive tract dysfunctions

- Improvement in the health and appearance of the skin

- Better nutrition from improved absorption and the internal generation of B vitamins.

- Protection against vaginosis and yeast infections

A good probiotic formula is absolutely essential for long-term intestinal health and long-term parasite control. When choosing a probiotic, look for the following characteristics:

Not all strains of beneficial bacteria are created equal. For each type of bacteria, there are recognized super strains. For example, super strains of acidophilus include DDS-1 and La-14. Choose a formula that uses only recognized super strains of beneficial bacteria — clearly identified as such on the label or in the company literature.

Not all strains of beneficial bacteria are created equal. For each type of bacteria, there are recognized super strains. For example, super strains of acidophilus include DDS-1 and La-14. Choose a formula that uses only recognized super strains of beneficial bacteria — clearly identified as such on the label or in the company literature.- A good probiotic formula will also contain the all-important supernatant — the medium the culture was grown in, or at least its active components. The supernatant, contains a multitude of beneficial byproducts of the growth process, including: vitamins, enzymes, antioxidants, and immune boosters. On the other hand, you need all of the water extracted from the supernatant for enhanced stability and longer shelf life.

- Which brings us to the question of how many live microorganisms are left in your formula when you actually use it. Pick up any probiotic formula, look at the label, and you’ll see something like: “Contains 13 billion live organisms per capsule at time of manufacture.” And that’s the problem: “at time of manufacture.” The die-off rate for probiotics can be astounding. Most formulas will experience a die-off approaching log 3 within just 60 days of manufacture. That means that the 13 billion you see on the label may be down to 13 million, or less, by the time you use it. Heat and moisture accelerate the die-off process, which is why most manufacturers recommend keeping your probiotic supply refrigerated.

- Water is removed and good probiotics are in fact concentrated in a two-fold process. In the first stage, the majority of water is removed via gentle concentration based upon centrifugation or microfiltration. This is an effective means to remove water. In the second stage, the remaining small amount of water is removed from the probiotic cells via the expensive process of freeze drying. Without the first stage of concentration, the cost to produce probiotics would jump significantly due to an extraordinary increase in freeze drying cycle times. Cheaper formulas simply heat the probiotics, which removes the water but also damages the cultures.

- Another trick used by the better manufacturers is to actually pack the capsules, at the time of encapsulation, with culture numbers that are actually substantially higher than listed on the label so that given normal die off over 18 months, the capsules will still deliver the listed numbers at the end of shelf life. (That’s what they do with my formula at Baseline Nutritionals.)

There are many beneficial bacteria that can be contained in a good probiotic, but two are preeminent. To maximize the probiotic benefits, look for a formula based on these two:

- L. acidophilus resides primarily in the small intestine and produces a number of powerful antimicrobial compounds in the gut (including: acidolin, acidolphilin, lactocidin, and bacteriocin). These compounds can inhibit the growth and toxin producing capabilities of some 23 known disease-causing pathogens (including: campylobacter, listeria, and staphylococci), as well as reduce tumor growth and effectively neutralize or inhibit carcinogenic substances.It’s also important to note that L. acidophilus is the primary beneficial bacteria in the vaginal tract. When the presence of the acidophilus is compromised, this allows the bad guys such as Gardnerella vaginalis or E. coli or Chlamydia to take over.

- Many researchers believe that declining levels of bifidobacteria in the large intestine actually mark the eventual onset of chronic degenerative disease. Bifidobacteria benefit the body in a number of ways. They consume old fecal matter, have the ability to remove cancer-forming elements (or the enzymes which lead to their formation), and protect against the formation of liver, colon, and mammary gland tumors.

More is not always better. Too many beneficial bacteria in one formula may find the bacteria competing with each other before they can establish themselves in separate areas of the intestinal tract. On the other hand, there are several other bacteria that are extremely beneficial in any probiotic formula. It is critical that a good formula contain some combination of these strains–or something comparable.

- L salivarius helps digest foods for a healthy intestinal tract and makes vital nutrients more assimilable. It also works to eat away encrusted fecal matter throughout the entire colon; it helps repair the intestinal tract by providing needed enzymes and essential nutrients; and it adheres to the intestinal wall, thereby forming a living matrix that helps protect the mucosal lining.

- L. rhamnosus is powerful for immune system support. It can increase the natural killing activity of spleen cells, which may help to prevent tumor formation. It boosts the ability of the body to destroy foreign invaders and other harmful matter by three times normal activity; and has been shown to increase circulating antibody levels by six to eight times.

- L. plantarum has the ability to eliminate thousands of species of pathogenic bacteria. It also has extremely high adherence potential for epithelial tissue and seems to favor colonizing the same areas of the intestinal tract that E. coli prefers — in effect, serving to crowd E. coli out of the body. At one time, plantarum was a major part of our diets (found in sourdough bread, sauerkraut, etc.), but is now virtually nowhere to be found.

- Note: a good probiotic formulation will contain a prebiotic bacteriophage or fructooligosaccharides (FOS) which help promote the growth of beneficial bacteria. For some friendly bacteria, such as the Bifidus, FOS can increase their effectiveness by a factor of 1,000 times or more!!

Supplementation with L. plantarum has the ability to eliminate thousands of species of pathogenic bacteria.

The bottom line is that we don’t continually supplement to fill an empty probiotic tank in our intestines. We supplement on a regular basis to continually keep our tank topped off so it never runs low. Is that a waste of money as the mainstream media has interpreted the study results? On some days, yes. But if you’re drinking chlorinated water or eating meat or dairy products that contain antibiotics or you’re under stress or just getting older, then no. In other words, if you’re alive today, supplementing with a quality probiotic formula is a simple, inexpensive, health insurance policy that makes all the sense in the world to protect yourself against a rainy day.

For more on probiotics, check out:

References

| ↑1 | Nadja B. Kristensen, Thomas Bryrup, Kristine H. Allin, et al. “Alterations in fecal microbiota composition by probiotic supplementation in healthy adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials.” Genome Medicine 20168:52. 10 May 2016. http://genomemedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13073-016-0300-5 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | http://www.sujajuice.com/product-category/pressed-probiotic-waters/ |

| ↑3 | http://ikuky.com/index.php |

| ↑4 | http://culturedcare.com/ |

| ↑5 | “Probiotics: In Depth.” NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Date Created: January 2007. Last Updated: October 2016. http://nccih.nih.gov/health/probiotics/introduction.htm |

| ↑6 | Lahti L, Salonen A, Kekkonen RA, Salojärvi J, Jalanka-Tuovinen J, Palva A, et al. “Associations between the human intestinal microbiota, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and serum lipids indicated by integrated analysis of high-throughput profiling data.” PeerJ. 2013;1:e32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3628737/ |

| ↑7 | Rampelli S, Candela M, Severgnini M, Biagi E, Turroni S, Roselli M, et al. “A probiotics-containing biscuit modulates the intestinal microbiota in the elderly.” J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(2):166–72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23364497 |

| ↑8 | Ferrario C, Taverniti V, Milani C, Fiore W, Laureati M, De Noni I, et al. “Modulation of fecal Clostridiales bacteria and butyrate by probiotic intervention with Lactobacillus paracasei DG varies among healthy adults.” J Nutr. 2014;144(11):1787–96. http://jn.nutrition.org/content/early/2014/09/03/jn.114.197723 |

| ↑9 | Bjerg AT, Sørensen MB, Krych L, Hansen LH, Astrup A, Kristensen M, et al. “The effect of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei L. casei W8® on blood levels of triacylglycerol is independent of colonisation.” Benef Microbes. 2015;6(3):263–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25273547 |

| ↑10 | Brahe LK, Le Chatelier E, Prifti E, Pons N, Kennedy S, Blædel T, et al. “Dietary modulation of the gut microbiota–a randomised controlled trial in obese postmenopausal women.” Br J Nutr. 2015;114(03):406–17. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4531470/ |

| ↑11 | Hanifi A, Culpepper T, Mai V, Anand A, Ford A, Ukhanova M, et al. “Evaluation of Bacillus subtilis R0179 on gastrointestinal viability and general wellness: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in healthy adults.” Benef microbes. 2014;6(1):19–27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25062611 |

| ↑12 | Simon MC, Strassburger K, Nowotny B, Kolb H, Nowotny P, Burkart V, et al. “Intake of Lactobacillus reuteri improves incretin and insulin secretion in glucose-tolerant humans: a proof of concept.” Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1827–34. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26084343 |

| ↑13 | Rampelli |

| ↑14 | Bjerg |

| ↑15 | Harbige LS, Pinto E, Allgrove J, Thomas LV. “Immune response of healthy adults to the ingested probiotic Lactobacillus casei Shirota.” Scand J Immunol. 2016 Oct 8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27718254 |

| ↑16 | Almeida CC, Lorena SL, Pavan CR, Akasaka HM, Mesquita MA. “Beneficial effects of long-term consumption of a probiotic combination of Lactobacillus casei Shirota and Bifidobacterium breve Yakult may persist after suspension of therapy in lactose-intolerant patients.” Nutr Clin Pract. 2012 Apr;27(2):247-51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22402407 |

| ↑17 | Simon |

| ↑18 | Zhang Z, Zhou Z, Li Y, et al. “Isolated exopolysaccharides from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG alleviated adipogenesis mediated by TLR2 in mice.” Sci Rep. 2016 Oct 27;6:36083. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27786292 |

| ↑19 | Currò D, Ianiro G, Pecere S, et al. “Probiotics, fibre and herbal medicinal products for functional and inflammatory bowel disorders.” Br J Pharmacol. 2016 Oct 3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27696378 |

| ↑20 | Oliveira VM, Santos SS, Silva CR, Jorge AO, Leão MV. “Lactobacillus is able to alter the virulence and the sensitivity profile of Candida albicans.” J Appl Microbiol. 2016 Sep 8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27606962 |

| ↑21 | Khailova L, Baird CH, Rush AA, et al. “Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment improves intestinal permeability and modulates inflammatory response and homeostasis of spleen and colon in experimental model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia.” Clin Nutr. 2016 Oct 1. pii: S0261-5614(16)31265-1. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27745813 |

| ↑22 | Ogita T, Bergamo P, Maurano F, et al. “Modulatory activity of Lactobacillus rhamnosus OLL2838 in a mouse model of intestinal immunopathology.” Immunobiology. 2015 Jun;220(6):701-10. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25623030 |

When I saw the title of the

When I saw the title of the article, claiming probiotics were virtually useless [what flashed to mind upon reading it], I nearly vomited.

Broad-spectrum, hi-potency Probiotics, are absolutely necessary, especially in today’s toxic milieu! It’s the single most effective method of fending off illnesses!

Having participated in some “research” conducted in one V.A. hospital, which was egregiously falsified, and having been privy to other “research”, I can attest to the fact that much “research” has increasingly been malfeasantly conducted to fool the public, and manipulate government agencies to give corporations the go-ahead to sell their poisons. IF that fails, they simply hide the results, and sell their junk anyway.

It’s critically important for people to learn as much as they can about their own health, to be their own best advocates, and teach your friends and family, in case they must be your advocate! This is needed, because of how risky it has become, to trust what mainstream medical industries spew at us.

It’s mind-boggling! Especially sensationalized ‘new developments’ that hit media like a blizzard, getting sound-bited into pure fiction.

Probiotics and fermented foods have been known for many decades, if not thousands of years, to be a _key_ to longevity and good health.

Don’t allow media to hype you into thinking they aren’t!

Caveat Emptor!

We agree! That is why Jon

We agree! That is why Jon wrote this article, to show the true benefits of probiotics–despite what the media says. Thank you for sharing your experience.

Probiotics from personal

Probiotics from personal experience. For my money the “probiotics craze” started a few years ago with a ground breaking study connecting probiotics and your gut to the brain and mental health…..by I believe UCLA School of Medicine.

My 80 year old Mom had just been in hospital for colon surgery, caught pneumonia and spent a month in the hospital. She was put on a HUGE regimen of the strongest antibiotics for weeks.

She went in a sharp lady and came out a month later a drooling mess….Sister and Aunt had her heading for a nursing home.

I took her back home and I got her what my research said were 2 good probiotics…she was back to her old self soon after and she passed away last year from smoking at 84 and her mind was still OK…Probiotics saved her life and also kept her at her home of 60+ years, which was her wish.

Out of the blue one day she said I want to leave this house feet first! And she did. Thanks in part to Probiotics…..

NO DOUBT ABOUT IT…Just sharing TRUTH.

Hi there,

Hi there,

I am so glad that I came across your testimonial about your mum, how did you take care of her by using the right type of probiotics. Can you let me knows which probiotic that you used for your mum. Really appreciate it.

Thank you.

Check out this link for our

Check out this link for our recommended probiotics: http://www.baselinenutritionals.com/products/probiotic-formula.php

When I saw the title of the

When I saw the title of the article, claiming probiotics were a waste of money, I nearly vomited too!

I hope you are talking about

I hope you are talking about the news title, not our article. Our title didn’t actually say probiotics were useless—just the reverse. The “Not” at the end of the title means you can throw out everything that came before it as not true—that you can throw out the current claims in the media that probiotics are a waste of money.

So, is the packaging and the

So, is the packaging and the transportation method important to ensure the potency and viability of the Probiotics? That would suggest the method should be a quick delivery and/or refrigeration in the transport, correct?

It’s not that simple. Keep in

It’s not that simple. Keep in mind that when you make yogurt, you incubate the culture at 110-115 degrees F to make it grow. The problem with heating it higher than that is not that the culture dies—it doesn’t—but that the milk scalds, which messes up the taste. You really need to get to about 180 degrees before you risk killing the culture. That said, sustained heat will accelerate the aging and die off of the culture…over time. So, bottom line, if the probiotics are stabilized (as explained in the article above), the heat sustained over a few days of normal delivery will not affect the life of the supplement as long as you refrigerate it after receiving it. The two exceptions are:

Are “pearl” probiotics useful

Are “pearl” probiotics useful?