So, what about breakfast? Some nutritionists call it the most important meal of the day. A new study that we’re going to cover in some detail in a bit says that skipping breakfast almost doubles your risk of death from heart disease. And yet, we frequently talk about the importance of fasting–in which breakfast seems to absolutely be skipped. No, wonder the Foundation gets so many people writing in saying they’re confused. Well, we’re going to see if we can resolve that confusion today.

Defining Breakfast

Why does breakfast have to be defined? Everybody knows what breakfast is–or do they? In fact, breakfast means vastly different things to different people and different cultures. For example:

- There’s the technical definition: the breaking of your evening fast which occurs while you sleep. And in fact, that’s where the word comes from: to “break fast.” It’s simply the first meal you eat after hours or days of not eating.

- For most Americans, breakfast means eggs, meat, and coffee or juice

- For others, it means a bowl of hot or cold cereal

- Or yogurt with added goodies and/or sugar

- Or a smoothie or food bar

- Or coffee and some form of donut or pastry

- In the UK, it can mean eggs, fried tomatoes, mushrooms and bread–and sausages (i.e., bangers)

- In Japan we’re talking fish, natto, rice, and miso soup

- In China, steamed buns stuffed with meat is not an unusual breakfast

- In Italy, it’s coffee and bread or rolls

- In Australia, it’s the big fry, which is basically the English breakfast, but with bacon instead of bangers

- In Russia, it’s porridge, bread, and ham

- In Iran, you’re more likely looking at bread and sheep-hoof stew

- And in South Africa, it might be porridge, bread, and coffee

You get the idea. There’s no such thing as a typical breakfast around the world. And it can be at any time of day 5-10 AM. And for those who work the night shift and sleep during the day, breakfast could be at 9:00 PM.

So, any study that deigns to make claims for breakfast needs to define what it means by breakfast. And unfortunately, most do not–leaving it vague or unspecified. And on that single point alone, they are rendered irrelevant. Which brings us to the study of the day.

Association of Skipping Breakfast with Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality

Cardiovascular disease — specifically heart disease and stroke — is the leading cause of death in the world, accounting for a combined 17.9 million deaths in 2016, according to the World Health Organization.1 “Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs).” WHO. 17 May 2017. (Accessed 8 May 2019.) http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) Not surprisingly, it’s also the leading cause of death in the United States. The working assumptions, then, for this study, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, was that skipping breakfast is common among U.S. adults and that limited evidence suggests that skipping breakfast is associated with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.2 Shuang Rong, Linda G. Snetselaar, Guifeng Xu, et al. “Association of Skipping Breakfast With Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Volume 73, Issue 16, April 2019. http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/73/16/2025 With that as its starting point, the authors sought to examine and verify that association of skipping breakfast with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.

Cardiovascular disease — specifically heart disease and stroke — is the leading cause of death in the world, accounting for a combined 17.9 million deaths in 2016, according to the World Health Organization.1 “Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs).” WHO. 17 May 2017. (Accessed 8 May 2019.) http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) Not surprisingly, it’s also the leading cause of death in the United States. The working assumptions, then, for this study, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, was that skipping breakfast is common among U.S. adults and that limited evidence suggests that skipping breakfast is associated with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.2 Shuang Rong, Linda G. Snetselaar, Guifeng Xu, et al. “Association of Skipping Breakfast With Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Volume 73, Issue 16, April 2019. http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/73/16/2025 With that as its starting point, the authors sought to examine and verify that association of skipping breakfast with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.

This was a prospective cohort study of a nationally representative sample of 6,550 adults 40 to 75 years of age who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES3) from 1988 to 1994. The frequency of breakfast eating was reported during an in-house interview. Death and underlying causes of death were ascertained by linkage to death records through end of the year 2011. The associations between breakfast consumption frequency and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality were then investigated using statistical analysis. It should be noted that although the NHANES3 survey got granular in terms of exactly what people ate and when, that data was not incorporated into the current study. In fact, neither the nature of the breakfast consumed nor the timing of that breakfast was clearly defined in the current study. But even at that, in the NHANES3 survey, it was the participants themselves who determined whether or not to call what they ate for their first meal of the day “breakfast “–both in terms of “what ” they ate it and when they ate it. Consider the evidence as noted in this extract from the survey’s Dietary Interviewers Manual.3 “NHANES-III DIETARYINTERVIEWER’S MANUAL.” September 1992. 4.3.12.1 p4-205. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes3/manuals/diet.pdf

“From midnight until (time of first meal code), you had nothing to eat or drink.” Pause a moment for an affirmative response from the respondent, then begin the review of the SP’s intake aloud, for example, “At 7:00 in the morning [or whatever time the participant noted in their survey for their first meal] you ate breakfast at home. You had one slice of toast with butter, and decaffeinated coffee with Equal …”Continue this procedure until you have reviewed the complete recall. ”

Thus, in terms of the survey, coffee and donuts qualify as having breakfast equally as does yogurt and fruit or ham and eggs. But, and this is even more important, if two participants woke up, went to work, and didn’t have their first meal until noon, one might call that meal breakfast in the survey and the other lunch. Which means, although the behavior is identical, the survey results show one skipping breakfast and the other not. Now again, the survey got more granular in terms of exactly what was eaten and when, but the study did not consider that granularity–only whether the respondents said that they had breakfast or not. Can you see how this might make the study’s results somewhat dubious?

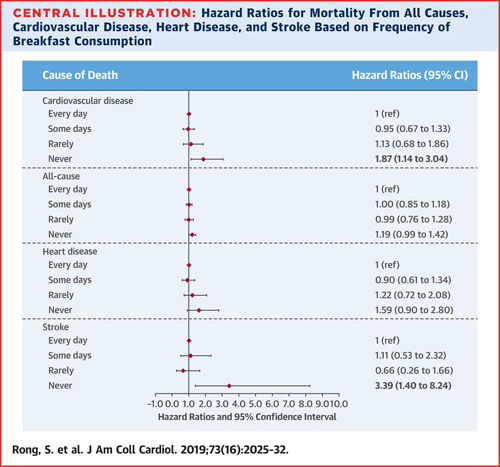

So, among the 6,550 participants in this study, 5.1% self-identified as never eating breakfast, 10.9% rarely ate breakfast, 25.0% ate breakfast some days, and 59.0% said they consumed breakfast every day (again, recognizing that both what was consumed and when for this self-defined breakfast was all over the map). Anyway, over the course of the study, 2,318 deaths occurred, including 619 deaths from cardiovascular disease. After adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, dietary and lifestyle factors, body mass index, and cardiovascular risk factors, participants who never ate breakfast compared with those eating breakfast every day had hazard ratios of 1.87 for cardiovascular mortality and 1.19 for all-cause mortality. Or to put that into English: those skipping breakfast had an 87% higher risk of heart disease-related death and stroke-related death compared with people who had breakfast every day, but curiously, only a 19% greater risk of dying from any cause.

According to the authors, cardiovascular risk factors include diabetes, hypertension, and lipid disorders. Based on the data they gathered, and supported by previous studies that consistently showed that skipping breakfast is related to those risk factors, the authors concluded that skipping breakfast is associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease–and that the study supports the benefits of eating breakfast in promoting cardiovascular health.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. According to Krista Varady, associate professor of nutrition at the University of Illinois, Chicago, who was not involved in the research, “The major issue [with the study] is that the subjects who regularly skipped breakfast also had the most unhealthy lifestyle habits. Specifically, these people were former smokers, heavy drinkers, physically inactive, and also had poor diet quality and low family income. ” All those factors put people at a much higher risk for cardiovascular disease. “I realize that the study attempted to control for these confounders, but I think it’s hard to tease apart breakfast skipping from their unhealthy lifestyle in general. “4 Jacqueline Howard. Skipping breakfast tied to higher risk of heart-related death, study finds.” CNN April 23, 2019. (Accessed 8 May 2019.) http://www.cnn.com/2019/04/22/health/skipping-breakfast-cardiovascular-death-study/index.html

And then there’s timed eating, currently a very popular form of intermittent fasting, that needs to be considered. Are those who skipped breakfast as a result of timed eating saying they skipped breakfast because they ate their first meal of the day at 10:00 AM, for example? But then, are they really skipping breakfast, or just eating it later. Remember, whenever they have it, it’s still the first meal of the day–the breaking of fast. Which brings us to…

Intermittent Fasting VS Breakfast

I’m a big fan of fasting. Digesting food is hard work.

- Fasting for one day provides a vacation for your body.

- Fasting, for as little as three days, “flips a regenerative switch” which prompts stem cells to create brand new white blood cells, essentially regenerating the entire immune system.

- And fasting for 5-7 days causes intelligent autolysis to kick in. At the point, your body begins harvesting and self-digesting the cells and parts of your body that are damaged or old–the inefficient parts, if you will, for energy. Then, when you start eating again, it replaces those parts with new, undamaged cells and tissue. That’s the primary benefit of fasting, now proven by science–a benefit not provided by your liver and kidneys, even on their best day, despite what fasting-deniers in the medical community might say.

But that’s not what we’re talking about today. We’re talking about a sub-category of intermittent fasting, an eating pattern where you cycle between periods of eating and fasting. In most programs, intermittent fasting says nothing about which foods to eat, but rather when you should eat them. There are several different intermittent fasting methods, all of which split the day or week into eating periods and fasting periods.

Intermittent fasting has gained considerable popularity over the past decade. There are two major subcategories of intermittent fasting:

- Fasting one to four days per week as in alternate day fasting5 Longo VD, Mattson MP. “Fasting: Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications.” Cell Metab. 2014;19(2):181–92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3946160/

- Time restricted feeding in which you fast every day, but only for about 16 hours a day.6 Longo VD, Panda S. “Fasting, Circadian Rhythms, and Time-Restricted Feeding in Healthy Lifespan.” Cell Metab. 2016;23(6):1048–59. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5388543/ , 7 Chaix A, et al. “Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges.” Cell Metab. 2014;20(6):991–1005. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4255155/

Both are problematic for the survey. If you’re fasting every other day, for example, you would show up in the study as eating breakfast only on “some days. ” But not that many people use that form of intermittent fasting. As I mentioned earlier, the form of fasting that is now very hot with celebrities, athletes, and the public at large is number 2 above–16/8 time-restricted eating–in which you eat for eight hours every day and fast for 16. For most people, that means starting your fast around 6 PM, continuing while you sleep, and then through the early morning. Finally, you break your fast and begin your eight-hour cycle of eating at around 10 AM when your 16 hours of fasting are up–continuing to eat whatever you want for the next eight hours before starting the cycle again.

Although this type of fasting does not go on long enough to initiate intelligent autolysis or regenerate the immune system, it does produce two benefits that have made it extremely popular.

- First and foremost, a 2018 study published in Nutrition and Healthy Aging found that 8-h time restricted feeding results in weight loss, without calorie counting8 Kelsey Gabel, Kristin K. Hoddy, Nicole Haggerty, et al. “Effects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: A pilot study.” Nutr Healthy Aging. 2018; 4(4): 345–353. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6004924/

- And a notable decrease in blood pressure

Anyway, depending on how you define it, eating your first food of the day at 10 AM means that, at least in the minds of many people, you’ve skipped breakfast and are into the no-man’s land between breakfast and lunch. But again, as we said earlier, it’s technically still breakfast because it’s the meal you’re using to break your fast.

So, How Does Intermittent Fasting Provide Its Health Benefits?

As we’ve already discussed, intermittent fasting will not rebuild your immune system–that takes a minimum of three days of consecutive fasting. And it won’t trigger intelligent autolysis, the most important benefit you can derive from fasting as that takes five to seven days of consecutive fasting. Nevertheless, it provides a whole range of lesser but still important health benefits, two of which we’ve already mentioned. Let’s look at those benefits in a little more detail.

As we’ve already discussed, intermittent fasting will not rebuild your immune system–that takes a minimum of three days of consecutive fasting. And it won’t trigger intelligent autolysis, the most important benefit you can derive from fasting as that takes five to seven days of consecutive fasting. Nevertheless, it provides a whole range of lesser but still important health benefits, two of which we’ve already mentioned. Let’s look at those benefits in a little more detail.

Intermittent Fasting and Weight Loss

Truth be told, this is often the primary reason people decide to give any form of intermittent fasting a try. And there is a great deal of research that indicates they will not be disappointed since intermittent fasting is quite effective in this regard. Essentially, it provides the same efficacy as calorie restriction,9 Trepanowski JF, Kroeger CM, Barnosky A, et al. “Effect of Alternate-Day Fasting on Weight Loss, Weight Maintenance, and Cardioprotection Among Metabolically Healthy Obese Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):930–938. http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2623528 but with two important extra benefits.

- Because of its intermittent nature, it never causes your body to slow its metabolism, which can cause severe weight rebounds when you finally stop, as happens with calorie restricted diets.

- And intermittent fasting is much easier to follow than caloric restriction, which requires you to stay on a program of self-denial day after day, for weeks at a time–which leaves many people feeling unsatisfied, unfulfilled, and unable to freely participate in social functions that involve eating.

So, exactly how does intermittent fasting, regardless of how it’s implemented, help you lose weight. Well, obviously, by virtue of the extended periods of non-eating, you tend to eat fewer calories, but there’s another equally important factor. When you’re not consuming food, your insulin and blood glucose levels drop. Do that for long enough–as happens during your fasting periods–and the reduced levels of insulin trigger your cells to release their glucose stores to provide energy. And burning up your glucose stores on a regular basis leads to weight loss.

Intermittent Fasting and Reduced Risk of Diabetes

High blood levels of insulin and glucose are known risk factors for diabetes. But, as we’ve discussed, intermittent fasting will lower your blood glucose levels as well as your fasting insulin levels and insulin resistance, thus lowering your risk of diabetes. It should be noted that time restricted eating is likely to prove superior in this regard as alternate day fasting is more likely to stimulate appetite and encourage binge eating on food days, which forces pancreatic cells to work harder on those days.

Intermittent Fasting and Central Nervous System (CNS) Health

Animal studies have found that intermittent fasting can suppress inflammation throughout the entire central nervous system.10 Andrea Rodrigues Vasconcelos, Paula Fernanda Kinoshita, Lidia Mitiko Yshii, et al. “Effects of intermittent fasting on age-related changes on Na,K-ATPase activity and oxidative status induced by lipopolysaccharide in rat hippocampus.” Neurobiology of Aging. Volume 36, Issue 5, May 2015, Pages 1914-1923. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0197458015001517 And more specifically, a 2017 article published in Ageing Research Reviews found that a number of studies have shown that intermittent fasting can reduce the risk of neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s Parkinson’s disease and stroke.11 Mark P. Mattson, Valter D. Longo, and Michelle Harvie. “Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes.” Ageing Res Rev. 2017 Oct; 39: 46–58. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5411330/

Intermittent Fasting and Cardiovascular Health

As we discussed earlier, studies have shown that intermittent fasting seems to have an ability to markedly lower blood pressure. As it turns out, this study does not exist in isolation. For example, studies have shown that intermittent fasting and exercise produce remarkably similar effects on heart rate and blood pressure. These effects of intermittent fasting on heart rate are not simply the result of caloric restriction, because rats maintained on intermittent fasting are only moderately calorie-restricted (10–20%) and yet exhibit greater reductions in resting heart rate than do mice on 40% daily caloric restriction.12 Mager DE, Wan R, Brown M, Cheng A, et al. “Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting alter spectral measures of heart rate and blood pressure variability in rats.” FASEBJ. 2006;20:631–637. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16581971

As we discussed earlier, studies have shown that intermittent fasting seems to have an ability to markedly lower blood pressure. As it turns out, this study does not exist in isolation. For example, studies have shown that intermittent fasting and exercise produce remarkably similar effects on heart rate and blood pressure. These effects of intermittent fasting on heart rate are not simply the result of caloric restriction, because rats maintained on intermittent fasting are only moderately calorie-restricted (10–20%) and yet exhibit greater reductions in resting heart rate than do mice on 40% daily caloric restriction.12 Mager DE, Wan R, Brown M, Cheng A, et al. “Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting alter spectral measures of heart rate and blood pressure variability in rats.” FASEBJ. 2006;20:631–637. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16581971

The available data suggests a scenario in which both intermittent fasting and exercise result in the enhancement of activity in brainstem neurons that triggers a consequent reduction in resting heart rate and blood pressure and increased heart rate variability.13 Wan R, Weigand LA, Bateman R, Griffioen K, Mendelowitz D, Mattson MP. “Evidence that BDNF regulates heart rate by a mechanism involving increased brainstem parasympathetic neuron excitability. J. Neurochem. 2014;129:573–580. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4137462/ Intermittent fasting has also been shown to enhance cardiovascular stress adaptation in rat models of uncontrollable stress.14 Wan R, Camandola S, Mattson MP. “Intermittent food deprivation improves cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responses to stress in rats.” J. Nutr. 2003;133:1921–1929. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12771340 The remarkably similar effects of exercise and intermittent fasting on heart rate and blood pressure suggest that both types of intermittent-bioenergetic-challenge can promote optimal cardiovascular health and fitness.

Conclusion: Breakfast VS Intermittent Fasting

So, what have we learned?

So, what have we learned?

- Despite what the recent study concluded, skipping breakfast is unlikely to cause health problems. The reason most people in the study who ate breakfast had healthier outcomes is simply because most people who ate breakfast in the study led healthier lives.

- Correspondingly, since most people in the study who “confessed ” to skipping breakfast also tended to lead generally unhealthy lifestyles, it is those lifestyles that are far more likely responsible for the health challenges they faced.

- And truth be told, most people who reported skipping breakfast did not actually skip it. Whenever you eat your first meal of the day, that’s breakfast. That’s when you’re breaking your fast. And if you think you’re skipping breakfast by grabbing a coffee and muffin at Starbucks on the way to work, you’re not. That was–unhealthy though it might be–your breakfast.

- 16/8 timed eating is an effective way to lose weight.

- It also helps lower blood pressure, reduces your risk of diabetes, and suppresses inflammation throughout your entire central nervous system–provided the rest of your lifestyle is healthy and provided the food you eat when breaking your fast is not coffee and donuts.

- Whenever you eat it, that first meal needs to be healthy since your body’s cells tend to suck up whatever you first eat when breaking fast. So,

- Skip the coffee and donuts, pastry, bagel, or toast meals. That’s just caffeine and high glycemic carbs.

- Skip the standard sugar sweetened breakfast cereals.

- Pancakes and waffles likewise don’t make the cut.

- And skip the low-protein, high-sugar food-bars and pop-tarts.

So, what is a healthy breakfast (at whatever time you choose to eat it)? Well, if you’re inclined to “breakfast ” types of food, then:

- Eggs are okay. But minimize the unhealthy side dishes such as country fried potatoes, processed breakfast meats, and muffins.

- Oatmeal is fine–although you might want to goose it up by adding a scoop of protein powder.

- High-protein food-bars also work.

- And then there are smoothies made with high-quality, hypoallergenic protein concentrates and fresh or frozen berries.

Also, it’s worth remembering, nothing but convention says that breakfast needs to look like breakfast–as people in many countries around the world can tell you.

- Have a protein fortified salad for your first meal of the day. If you’re vegetarian, go for quinoa or buckwheat as your protein boosters.

- Or fresh fish and a vegetable side.

- You get the idea. Anything that you eat for the first meal of the day is breakfast, even if most people wouldn’t consider it such. Just make sure it’s clean, as organic as possible, and nutritious.

By the way, if you’re curious as to what I eat for breakfast and when:

- Since I do my daily exercise workout first thing in the morning before eating, by the time I’m done exercising and dealing with my first round of email (I average about 200 emails a day), I’m looking at between 10 and 11 in the morning before I sit down for breakfast.

- Sometimes, I opt for 1/3 of a high protein food bar that I cover in raw almond butter.

- Other times, it’s a smoothie made with frozen strawberries, raspberries, half a banana, almond milk (excuse me–beverage), and fortified with a scoop of my own formula: Nutribody Protein®. But really, what other protein powder did you think I would use?

- And on Sundays, Kristen and I will indulge in brunch centered around an egg dish, which varies depending on what we want that day.

- And by the way, if you’re buying eggs, forget conventional and cage free eggs (cage free doesn’t mean what you think it means). Instead, look for Pasture Raised, Certified Humane® eggs.

So, there you go. Everything you ever wanted to know about breakfast–and probably a whole lot more.

References

| ↑1 | “Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs).” WHO. 17 May 2017. (Accessed 8 May 2019.) http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Shuang Rong, Linda G. Snetselaar, Guifeng Xu, et al. “Association of Skipping Breakfast With Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Volume 73, Issue 16, April 2019. http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/73/16/2025 |

| ↑3 | “NHANES-III DIETARYINTERVIEWER’S MANUAL.” September 1992. 4.3.12.1 p4-205. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes3/manuals/diet.pdf |

| ↑4 | Jacqueline Howard. Skipping breakfast tied to higher risk of heart-related death, study finds.” CNN April 23, 2019. (Accessed 8 May 2019.) http://www.cnn.com/2019/04/22/health/skipping-breakfast-cardiovascular-death-study/index.html |

| ↑5 | Longo VD, Mattson MP. “Fasting: Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications.” Cell Metab. 2014;19(2):181–92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3946160/ |

| ↑6 | Longo VD, Panda S. “Fasting, Circadian Rhythms, and Time-Restricted Feeding in Healthy Lifespan.” Cell Metab. 2016;23(6):1048–59. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5388543/ |

| ↑7 | Chaix A, et al. “Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges.” Cell Metab. 2014;20(6):991–1005. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4255155/ |

| ↑8 | Kelsey Gabel, Kristin K. Hoddy, Nicole Haggerty, et al. “Effects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: A pilot study.” Nutr Healthy Aging. 2018; 4(4): 345–353. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6004924/ |

| ↑9 | Trepanowski JF, Kroeger CM, Barnosky A, et al. “Effect of Alternate-Day Fasting on Weight Loss, Weight Maintenance, and Cardioprotection Among Metabolically Healthy Obese Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):930–938. http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2623528 |

| ↑10 | Andrea Rodrigues Vasconcelos, Paula Fernanda Kinoshita, Lidia Mitiko Yshii, et al. “Effects of intermittent fasting on age-related changes on Na,K-ATPase activity and oxidative status induced by lipopolysaccharide in rat hippocampus.” Neurobiology of Aging. Volume 36, Issue 5, May 2015, Pages 1914-1923. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0197458015001517 |

| ↑11 | Mark P. Mattson, Valter D. Longo, and Michelle Harvie. “Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes.” Ageing Res Rev. 2017 Oct; 39: 46–58. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5411330/ |

| ↑12 | Mager DE, Wan R, Brown M, Cheng A, et al. “Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting alter spectral measures of heart rate and blood pressure variability in rats.” FASEBJ. 2006;20:631–637. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16581971 |

| ↑13 | Wan R, Weigand LA, Bateman R, Griffioen K, Mendelowitz D, Mattson MP. “Evidence that BDNF regulates heart rate by a mechanism involving increased brainstem parasympathetic neuron excitability. J. Neurochem. 2014;129:573–580. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4137462/ |

| ↑14 | Wan R, Camandola S, Mattson MP. “Intermittent food deprivation improves cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responses to stress in rats.” J. Nutr. 2003;133:1921–1929. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12771340 |

I’ve been reading Jon Barron’s articles for about seven years now and I’ve learned so much. Breaking down this current confusion surrounding breakfast and fasting was so helpful and as usual everything stated makes unbiased logical sense. Thank you for taking the time to educate the public and thank you for making high quality products.