Early last month, a study that measured the long-term changes in resting metabolic rate (RMR) and body composition for participants of “The Biggest Loser” competition was published in the Obesity research journal.1 Erin Fothergill, Juen Guo1, Kevin Hall, et al. “Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition.” Obesity online 2 MAY 2016. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/oby.21538/full The study tracked 14 contestants from the reality show and confirmed that the massive weight-loss achieved on the show appears to be almost impossible to maintain. Even worse, the study confirmed what many former participants had been saying for years: that the accelerated weight-loss produced by the show is not only hard to maintain but that in fact it’s both easy and likely that former contestants will re-gain all the weight that was lost and more. Although this seems to be a surprise to the show’s money hungry producers, the public that devours the show, and the media that feeds on it, it shouldn’t be. Based on what we’ve known about weight-loss for decades, the results were highly predictable. As the old TV ads used to say, “You can’t fool Mother Nature.”

To make matters worse, although the study captured legitimate data and correctly interpreted that data, it contains a hole in it so big that you could drive a Caterpillar 797F dump truck through it. And it means that the study’s conclusions, although correct up to a point, absolutely fall far short in their assessment of what lessons we can draw from those conclusions. And unfortunately, it’s the false assessment that the media ran with.

We’ll cover all of that in a bit, but first let’s take a closer look at the study.

Persistent Metabolic Adaptation As Seen on the “The Biggest Loser”

The essence of the study was simple. First, body composition was measured six years after the season being studied ended using the same model, dual-energy X-ray-absorptiometry scanner that was used to make the original measurements during the competition. This allowed for an apples to apples comparison. And second, the participants’ resting metabolic rate (RMR) was determined both at the end of the 30-week competition and 6 years later. For the purposes of the study, metabolic adaptation was defined as the residual RMR after adjusting for changes in body composition and age.

Of the original 16 “Biggest Loser” competitors that season, 14 agreed to participate in the study–six men and eight women.2 Johanssen DL, Knuth ND, Huizenga R, et al. “Metabolic slowing with massive weight-loss despite preservation of fat-free mass.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:2489–2496. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3387402/ During the 30-week competition, they lost an average of 58 lbs., 43% of their body fat (49% down to 28%) and saw an average 19 point drop in their BMI. Unfortunately, after six years, most of the subjects had regained a significant amount of the weight they had lost during the competition with a mean weight-loss now showing just 11.9 lbs., although there was a wide degree of individual variation. All but one subject regained at least some of the weight lost during the competition; however, five subjects were within 1% of their original baseline weight or above. On average, at their six year follow up, the participants had put back on 41 of the 58 lbs. they had lost, taken their body fat levels back up to 45%, and their BMI up to 43%.

Let’s be clear. Some or even most of this rebound would be expected given that the “former” competitors were now left to their own devices, no longer in a controlled environment, no longer under the authoritarian control of their “coaches,” no longer under public scrutiny, and no longer with any financial incentives to motivate them. And if that’s all the study found, it would not be that big a deal–other than to expose the fallacy of yet another reality TV show. But according to the study’s authors, the reason for this rebound goes far deeper than any expected causes. According to the researchers, the participants had experienced abnormally excessive slowing of their metabolism as a result of their participation in the competition. Even worse, the study found that despite substantial weight regain in the six years following participation in “The Biggest Loser”, the participants’ RMR remained suppressed at the same average level as at the end of the weight-loss competition. Mean RMR after 6 years was ∼500 kcal/day lower than expected based on the measured body composition changes and the increased age of the subjects. In other words, they were burning 500 calories less per day than they were at the start of the competition. 500 calories a day translates to about a pound a week. And even worse than that, those participants who had been most successful at maintaining lost weight after six years also experienced greater ongoing metabolic slowing. In technical terms, these observations, according to the researchers, suggest that metabolic adaptation is a proportional but incomplete response to contemporaneous efforts to reduce body weight from its defended baseline or “set-point” value.3 Speakman JR, Levitsky DA, Allison DB, et al. “Set-points, settling points and some alternative models: theoretical options to understand how genes and environments combine to regulate body adiposity.” Dis Models Mech 2011;4:733–745. http://dmm.biologists.org/content/4/6/733

In less technical terms:

- Former “Biggest Loser” participants had slower metabolisms than people of comparable age and body composition who had never lost an extreme amount of weight. And these slowed metabolisms persisted even years after participating in the competition.

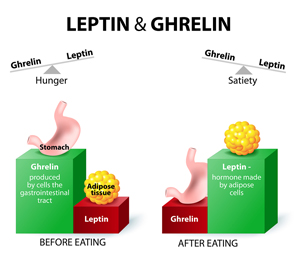

- And to make matters worse–yes it gets worse– the leptin levels of “The Biggest Loser” participants had plummeted during their time on the show and never fully returned to their pre-weight-loss numbers. This is critical because leptin is the “satiety hormone” which lets your body know when you’ve eaten enough.

According to the researchers, these two factors create a perfect storm for weight regain because the body is now slower to burn calories at the same time that lowered leptin levels make you feel like you need to keep eating no matter how much you eat. And this is the story the press ran with. Indeed, the findings as they were first reported in the New York Times were accompanied by distressing testimony from former contestants who spoke of an overwhelming hunger and food cravings they couldn’t control.4GINA KOLATA. “After ‘The Biggest Loser,’ Their Bodies Fought to Regain Weight.” The New York Times May 2, 2016. (Accessed 29 May 2016.) http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/02/health/biggest-loser-weight-loss.html

And beyond that, the meta-conclusion of the study that the press ran with is that the more overweight you are, the more fruitless your attempts to lose weight. In other words, everyone who loses weight goes through the same metabolic slowdown and leptin deficits, but the more you lose (as was the case with the show participants), the bigger the slowdown and the bigger the deficits–thus, the more difficult it will be to keep the weight off. Or in other words, in the case of trying to lose weight if you are extremely obese, you’re doomed to failure–but it’s not your fault. Simply, you’re metabolically screwed.

But as I mentioned at the beginning of the newsletter, this study had a hole so big in it that you could drive a Caterpillar 797F through it. Let’s take a look at that hole.

The Hole in the Study

In simple terms, the study doesn’t recognize that there was anything special about the way people on the show lost their weight that might contribute to the metabolic slowing and leptin deficiencies that might not be experienced by people losing weight in a different manner. The researchers’ conclusion is that all approaches to losing weight produce identical metabolic results. Or more precisely, their conclusion is that those problems stem exclusively from the profound obesity that all the contestants shared at the start. The study then extrapolated their limited conclusions to a more general meta-conclusion that these problems will likely be experienced by every other overweight person who tries to lose weight regardless of how they approach that weight-loss. Which brings us to the hole in the study.

Different approaches to weight-loss produce different metabolic results. @BaselineHealth

Different approaches to weight-loss produce different metabolic results. @BaselineHealth

And that is that it treats all people and all forms of weight-loss as one and the same. In fact, numerous studies show that they are not, and that those differences matter. People are different, and different approaches to weight-loss produce different metabolic results. Here are some of the key differences ignored by the study.

- The way in which you lose weight matters.

- How long you hold that weight-loss steady matters.

- Your starting weight matters–but not in the way the researchers think.

- Regaining much of the weight you lost may not qualify as failure.

- There’s more to hunger hormones than simply levels.

- It’s not about short-term weight-loss. It’s about long-term lifestyle.

The Way/Rate in Which You Lose Weight Matters

The biggest loser diet puts people on a program that runs around 1200 calories a day or less–every single day.5 Kara Mayer Robinson. “The Biggest Loser Diet.” WebMD March 28, 2016. (Accessed 27 May 2016.) http://www.webmd.com/diet/a-z/biggest-loser-diet Their exercise workouts expend anywhere from 3500-7000 calories a day.6 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I27ULudvWEk That creates a severe calorie deficit, which leads to the extreme weight-loss experienced by the participants. As they say in Yiddish, this is mashugana (crazy)! Based on everything we know about weight-loss, you never want to go on an extreme calorie deficit for more than one or two days at a time. Any longer than that and your metabolism begins to reset to starvation mode. It learns to maintain its weight on fewer calories. If you want to lose weight, aim for doing the 1200 calorie diet every other day. That accomplishes two things. One, everyone can diet for one day at a time. Two, it prevents your metabolism from dropping. Note: That doesn’t mean pig out on the non-diet days. Eat sensibly. Go for 1600 calories. That’s one third more food. But make sure you enjoy what you eat so you can do the 1200 calories again the next day. If you do that, then you’re averaging only 1400 calories a day and should be able to lose close to a pound a week with moderate exercise at that rate. Cut that loss in half and you’re still looking at two pounds a month–or 24 lbs. in a year.

How Long You Hold that Weight-loss Steady Matters

Another problem with the biggest loser program is that at no point did the participants stabilize their weight-loss. This is crucial. They were either losing weight (while participating in the program) or gaining weight (once they left the program). This runs headlong into the set-point theory of weight-loss.

According to the set-point theory, there is a control system built into every person dictating how much fat he or she should carry — a kind of thermostat for body fat. Some individuals have a high setting, others have a low one. According to this theory, body fat percentage and body weight are matters of internal controls that are set differently in different people.

According to the set-point theory, once a normal weight for your body is established, the set-point keeps that weight fairly constant and resists attempts to change it–either up or down. For example, studies show that when you try to abruptly force your set-point lower, depression and lethargy may set in as a way of slowing you down and reducing the number of calories you expend. Also, the original set-point will tend to drive your weight back up the moment you relax on your weight-loss regimen.

The set-point theory was originally developed in 1982 by William Bennett, M.D. and Joel Gurin to explain why repeated dieting is unsuccessful in producing long-term change in body weight or shape.7 http://www.amazon.com/Dieters-Dilemma-Eating-Less-Weighing/dp/0465016537/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1464407257&sr=8-1&keywords=The+Dieter%27s+Dilemma%3A+The+Setpoint+Theory+of+Weight+Control Going on a weight-loss diet that attempts to overpower the set-point–rather than gently massaging it down–reveals the set-point to be a tireless obstacle to weight-loss. It appears there are four keys to successfully coaxing your set-point lower VS trying to overpower it.

- A sustained increase in physical activity seems to lower the setting. This key was realized by the contestants on “The Biggest Loser.”

- Don’t lose weight too quickly as this triggers the set-point to resist your attempts at weight-loss. This point was absolutely violated by “The Biggest Loser” contestants as the goal was to “win the completion” by losing more weight, faster than anyone else in the competition.

- Scientific evidence supports losing no more than 10% of your body weight in any single attempt at weight loss. It turns out that the body’s set-point and its many regulatory hormones dictate the effectiveness of the 10% mark. Quite simply, that’s the amount of weight you can lose before your body starts to fight back. Many clinical studies have confirmed this phenomenon. Of course, some people can lose more than 10% at a time, but precious few can then maintain that loss. This key also was violated big-time by the contestants.

- And finally, it is crucial that you hold the new weight steady for at least six months to allow your body to establish the new weight as its new set-point. And once again, this key too was violated by the majority of the contestants as they were either losing weight while competing or gaining weight once the competition was over. With their weight constantly in flux, there was no opportunity for their bodies to establish a new, lower set-point. In other words, their original set-point remained unchanged, and their bodies immediately began to reach back to that weight level the moment they were given a chance. Note: once you’ve stabilized your 10% weight-loss for six months and thus established a new set-point, you can then restart your weight-loss regimen and lose another 10%–repeating the process as often as needed to achieve your ultimate weight goal and its corresponding set-point.

This approach takes longer, but it works with your body’s metabolism rather than fighting it. It’s weight-loss built for the long-term, not a reality TV show.

Scientific evidence supports losing no more than 10% of your body weight at a time. @BaselineHealth

Scientific evidence supports losing no more than 10% of your body weight at a time. @BaselineHealth

Your Starting Weight Matters–but not in the Way the Researchers Think

We’ve previously discussed the fact that muscle burns more calories than fat. Muscle is active. It burns calories even at rest. Fat cells, on the other hand are passive storage cells. They do not burn calories when the body is at rest. However, there is a surprising twist to this narrative. The more you weigh–regardless of whether that weight is fat or muscle–the more energy it takes your body to function. This means that a heavier person will burn more calories doing the same activities as a lighter person. This applies both when you are at rest and when you are performing physical activities. It also applies to people who are obese, as well as to bodybuilders with high muscle mass. To put this in more prosaic terms: if there’s less of you to move around, to pump blood through, and to keep at 98.6 degrees, you’re going to burn fewer calories than would be required by a larger version of yourself.

We’ve previously discussed the fact that muscle burns more calories than fat. Muscle is active. It burns calories even at rest. Fat cells, on the other hand are passive storage cells. They do not burn calories when the body is at rest. However, there is a surprising twist to this narrative. The more you weigh–regardless of whether that weight is fat or muscle–the more energy it takes your body to function. This means that a heavier person will burn more calories doing the same activities as a lighter person. This applies both when you are at rest and when you are performing physical activities. It also applies to people who are obese, as well as to bodybuilders with high muscle mass. To put this in more prosaic terms: if there’s less of you to move around, to pump blood through, and to keep at 98.6 degrees, you’re going to burn fewer calories than would be required by a larger version of yourself.

Let’s get specific as to how many fewer calories we’re talking about. Thirty minutes of high-impact aerobics burns 300 calories for a person weighing 125 pounds, but it will burn 372 calories for someone who weighs 150 pounds.8 “Calories burned in 30 minutes for people of three different weights.” Harvard Health Publications, Harvard Medical School. July 1, 2004, Updated: January 27, 2016. (Accessed 27 May 2016.) http://www.health.harvard.edu/newsweek/Calories-burned-in-30-minutes-of-leisure-and-routine-activities.htm A person who weighs 185 pounds, on the other hand, burns 444 calories from thirty minutes of high-impact aerobics. A half hour of dancing, meanwhile, can burn 165 calories if you weigh 125 pounds, but if you weigh 150 pounds you’ll burn 205 calories. At 185 pounds this same activity can shed 244 calories.

To better understand this, walk up and down a flight of stairs and note how you feel. Then fill a backpack with 50 lbs. of weight, strap it on, and take to the stairs again. Then ask yourself: which version of the stair climbing activity required more effort and left you shorter of breath? It’s really that simple. As you lose weight, your metabolism is going to slow down simply because you’ve taken weight out of your metaphorical backpack. So yes, as the study found, the people who had gained back the least weight would have the slowest metabolism–as it should be.

Regaining Much of the Weight You Lost May Not Qualify As Failure

After six years, most of the subjects had regained a significant amount of the weight they had lost during the competition, although there was a wide degree of individual variation and a mean weight-loss of 12-17 lbs. That certainly is disappointing, but does it necessarily qualify as failure? When you think about it, on average, the contestants as a whole had maintained a weight-loss that ranged from 58 lbs. (where they ended the competition) to some 12-17 lbs. still lost six years later. That’s actually a substantial difference and a huge health benefit to the body for six years of their lives. And keep in mind that if they had never entered the competition, they would likely have continued to gain weight from their starting point since they would have continued eating the same as always and exercised as little as always. That means that in reality the weight differential of 12-17 lbs. after six years is more likely in the range of 30-40 lbs., once you factor in the weight they would have gained if they had never entered the competition. A 30-40 lb. differential after six years cannot be qualified as failure.

There’s More to Hunger Hormones than Simply Levels

According to the study, one of the major negatives discovered is that the leptin levels of “The Biggest Loser” participants plummeted during their time on the show and never fully returned to their pre-weight-loss numbers. This is critical because leptin is the “satiety hormone” that lets your body know when you’ve eaten enough. But this conclusion by the researchers, although factually correct, is misleading. It only tells half the story. Leptin is produced in your body’s white fat cells. Not surprisingly then, the amount of leptin in your bloodstream is proportional to the amount of body fat you have. As you lose fat, leptin levels will drop. As you regain fat, leptin levels will rise. But…exercise improves your body’s leptin sensitivity. In other words, the more you exercise and build muscle mass, the less leptin it takes to control appetite at the same level.9 Dyck DJ. “Leptin sensitivity in skeletal muscle is modulated by diet and exercise.” Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2005 Oct;33(4):189-94. http://leptinresearch.org/pdf/cln_leptin_sensitivity_in_skeletal_muscle_is_modulated_by_diet_and_exercise.pdf Comparing leptin levels without factoring in exercise levels, changes in muscle mass, and your body’s improved leptin sensitivity is essentially meaningless.

According to the study, one of the major negatives discovered is that the leptin levels of “The Biggest Loser” participants plummeted during their time on the show and never fully returned to their pre-weight-loss numbers. This is critical because leptin is the “satiety hormone” that lets your body know when you’ve eaten enough. But this conclusion by the researchers, although factually correct, is misleading. It only tells half the story. Leptin is produced in your body’s white fat cells. Not surprisingly then, the amount of leptin in your bloodstream is proportional to the amount of body fat you have. As you lose fat, leptin levels will drop. As you regain fat, leptin levels will rise. But…exercise improves your body’s leptin sensitivity. In other words, the more you exercise and build muscle mass, the less leptin it takes to control appetite at the same level.9 Dyck DJ. “Leptin sensitivity in skeletal muscle is modulated by diet and exercise.” Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2005 Oct;33(4):189-94. http://leptinresearch.org/pdf/cln_leptin_sensitivity_in_skeletal_muscle_is_modulated_by_diet_and_exercise.pdf Comparing leptin levels without factoring in exercise levels, changes in muscle mass, and your body’s improved leptin sensitivity is essentially meaningless.

It’s Not about Short-term Weight-loss

This is the biggest problem I have with both “The Biggest Loser” competition and the study. Neither differentiates between losing weight quickly VS losing it for the long-term. I understand why “The Biggest Loser” does that. It’s about ratings. Keeping the weight off long-term is irrelevant to the show’s ratings. All that matters is losing that weight as fast as possible. But as we’ve discussed, in order to allow your body to keep reestablishing a lowered set-point, you need to restrict your weight-loss at any one time to about 10% of your total weight and then hold it for six months before repeating the process. I understand why this is not very appealing to a competitive TV show built on the idea of showcasing the most dramatic weight-loss numbers in the shortest amount of time. Unfortunately, while that may be great for ratings, it’s terrible for long-term weight-loss. On the other hand, there is no excuse for the study’s authors to make the same generalization and conclude that what happened to the competitors applies to people who lose large amounts of weight correctly.

Conclusion

If you’re severely overweight, it would be tempting to take the findings of the Obesity study as an excuse to give up. If people who lose a substantial amount of weight are guaranteed to gain it all back–and then some–what’s the point of even trying?

But that would be the wrong conclusion to walk away with. Other studies–all based on losing weight in a different manner, of course–find the metabolic penalty (the reduction in the number of calories you burn every day) for weight-loss to be much less than the 500 calories seen in the “The Biggest Loser” study. In fact, a number of studies even find it to be non-existent. For example, a 2009 study published in the British Journal of Nutrition that placed obese men on a supervised diet along with an exercise program found the penalty to be less than 200 calories per day.10 Tremblay A, Chaput JP. “Adaptive reduction in thermogenesis and resistance to lose fat in obese men.” Br J Nutr. 2009 Aug;102(4):488-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19660148

Stefan GJA Camps, Sanne PM Verhoef, Klaas R Westerterp. “Weight-loss, weight maintenance, and adaptive thermogenesis.” Am J Clin Nutr May 2013 vol. 97 no. 5 990-994. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/97/5/990.long And a 2013 study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition that was based on a very-low-energy diet for 8 weeks, followed by a 44-week period of weight maintenance, placed the penalty at less than 100 calories per day.11 Stefan GJA Camps, Sanne PM Verhoef, Klaas R Westerterp. “Weight-loss, weight maintenance, and adaptive thermogenesis.” Am J Clin Nutr May 2013 vol. 97 no. 5 990-994. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/97/5/990.long Again remember, there is going to be a slowdown in metabolism simply because you now have less weight to carry around.

But there are also several studies that found no penalty. For example, a 2008 study of women placed on a high protein, low calorie diet who lost 5% of their body weight (half the 10% guideline that we spoke of earlier) experienced no “observable” metabolic penalty.12 Pasiakos SM, Mettel JB, West K, et al. “Maintenance of resting energy expenditure after weight-loss in premenopausal women: potential benefits of a high-protein, reduced-calorie diet.” Metabolism. 2008 Apr;57(4):458-64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18328345 And perhaps most significant was the 2012 meta-study that looked at 2,977 subjects from 90 published studies and concluded, “This analysis does not support the notion of a greater than predicted decrease in resting EE [energy expenditure] after weight-loss.”13 Alexander Schwartz, Jennifer L. Kuk, Gilles Lamothe, Éric Doucet. “Greater Than Predicted Decrease in Resting Energy Expenditure and Weight-loss: Results From a Systematic Review.” Obesity Volume 20, Issue 11, 2307–2310, November 2012. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1038/oby.2012.34/full (By “predicted” they’re talking about the lowered expenditure of calories simply because you’ve lightened the load in your “backpack.”

At the very least, the results of “The Biggest Loser” study place it in the outlier category in terms of metabolic penalty. But that aside, the study’s assumption that the “The Biggest Loser” outcomes are extrapolatable to all other weight-loss programs is simply unsupportable and renders its conclusions meaningless. The bottom line is that if you’re looking to lose a large amount of weight:

- Do it 10% at a time or less. (see above)

- Lock that loss in for six months before repeating. (see above)

- Do not go on a low calorie program for more than two days at a time. In fact, every other day or less is better.

- Incorporate regular, short juice fasts on your low calorie days to allow your body to clean out and rebuild.

- Exercise at least one-hour a day to build muscle mass, increase brown fat levels, and maintain your BMR.

- Shift to a modified Mediterranean diet, not just for losing weight, but as a better way to live for the rest of your life.

- Follow the guidelines in Making sense of weight-loss.

References

| ↑1 | Erin Fothergill, Juen Guo1, Kevin Hall, et al. “Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition.” Obesity online 2 MAY 2016. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/oby.21538/full |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Johanssen DL, Knuth ND, Huizenga R, et al. “Metabolic slowing with massive weight-loss despite preservation of fat-free mass.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:2489–2496. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3387402/ |

| ↑3 | Speakman JR, Levitsky DA, Allison DB, et al. “Set-points, settling points and some alternative models: theoretical options to understand how genes and environments combine to regulate body adiposity.” Dis Models Mech 2011;4:733–745. http://dmm.biologists.org/content/4/6/733 |

| ↑4 | GINA KOLATA. “After ‘The Biggest Loser,’ Their Bodies Fought to Regain Weight.” The New York Times May 2, 2016. (Accessed 29 May 2016.) http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/02/health/biggest-loser-weight-loss.html |

| ↑5 | Kara Mayer Robinson. “The Biggest Loser Diet.” WebMD March 28, 2016. (Accessed 27 May 2016.) http://www.webmd.com/diet/a-z/biggest-loser-diet |

| ↑6 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I27ULudvWEk |

| ↑7 | http://www.amazon.com/Dieters-Dilemma-Eating-Less-Weighing/dp/0465016537/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1464407257&sr=8-1&keywords=The+Dieter%27s+Dilemma%3A+The+Setpoint+Theory+of+Weight+Control |

| ↑8 | “Calories burned in 30 minutes for people of three different weights.” Harvard Health Publications, Harvard Medical School. July 1, 2004, Updated: January 27, 2016. (Accessed 27 May 2016.) http://www.health.harvard.edu/newsweek/Calories-burned-in-30-minutes-of-leisure-and-routine-activities.htm |

| ↑9 | Dyck DJ. “Leptin sensitivity in skeletal muscle is modulated by diet and exercise.” Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2005 Oct;33(4):189-94. http://leptinresearch.org/pdf/cln_leptin_sensitivity_in_skeletal_muscle_is_modulated_by_diet_and_exercise.pdf |

| ↑10 | Tremblay A, Chaput JP. “Adaptive reduction in thermogenesis and resistance to lose fat in obese men.” Br J Nutr. 2009 Aug;102(4):488-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19660148 Stefan GJA Camps, Sanne PM Verhoef, Klaas R Westerterp. “Weight-loss, weight maintenance, and adaptive thermogenesis.” Am J Clin Nutr May 2013 vol. 97 no. 5 990-994. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/97/5/990.long |

| ↑11 | Stefan GJA Camps, Sanne PM Verhoef, Klaas R Westerterp. “Weight-loss, weight maintenance, and adaptive thermogenesis.” Am J Clin Nutr May 2013 vol. 97 no. 5 990-994. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/97/5/990.long |

| ↑12 | Pasiakos SM, Mettel JB, West K, et al. “Maintenance of resting energy expenditure after weight-loss in premenopausal women: potential benefits of a high-protein, reduced-calorie diet.” Metabolism. 2008 Apr;57(4):458-64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18328345 |

| ↑13 | Alexander Schwartz, Jennifer L. Kuk, Gilles Lamothe, Éric Doucet. “Greater Than Predicted Decrease in Resting Energy Expenditure and Weight-loss: Results From a Systematic Review.” Obesity Volume 20, Issue 11, 2307–2310, November 2012. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1038/oby.2012.34/full |

Dr. Valter Longo suggests a 3

Dr. Valter Longo suggests a 3 day complete fast every 6 months to strengthen the immune system, getting rid of weak ineffective white blood cells through autophaghy. I have followed this procedure several times, as have many other people, without harm to my metabolism, in spite of the fact that it violates the rule to do a low calorie diet for no longer than two days at a time. However, I am of normal weight and any weight loss as a result of the fast was quickly regained.

Even though I’ve never had

Even though I’ve never had any problem with weight, the How To Maintain Weight Loss article hooked me after reading a few paragraphs. There is a lot of sensible information that made complete sense to me. How one can stabilize the set point is critical to keeping the weight off. The 10 percent idea, one I’ve never heard before, is critical to losing weight and keeping it off too.

There’s a photo in a book sold on Amazon.com with the clever title of I Do It with the Lights Off. The photo on the cover with a satisfied obese woman hints what the contents of the book is about. But the fat women who go to the ballroom dances I attend don’t often appear that satisfied when they get only a few dances. Intelligent weight loss could make a difference for these women and many others.

I wish I could copy this article and give it to people who need it. Of course I won’t do that because I’d feel a wave of hatred directed toward me.

why can’t this article be out

why can’t this article be out in mainstream media where it belongs?

But Jon, what about the

But Jon, what about the centuries of data, back to the 1850s, that show sugar & starch intake as the driver of weight gain, and insulin as the mechanism that stops fat-burning? In hundreds, maybe thousands, of tests now it’s been shown that calorie deficits, while still eating sugars & starches, reduces metabolism because the body will hang onto its “reserves” when it thinks it’s starving. And while exercise builds lean muscle, it contributes very little to fat-burning, especially when regularly flowing insulin is regularly inhibiting that burning. It’s no wonder those “big losers” gained back their weight! Their Nazi-like environment kept them starved, but their lowered metabolism kept them constantly hungry — so of course they gained when set free, even if they ate great food (not junk). Their body”s set point hadn’t changed, due to the maintenance of insulin levels.

The key, I’ve discovered, is to eliminate starches & sugars (only carbs remaining are green veggies, nuts & berries), and to greatly increase healthy fats, even above the level of protein, because protein is broken down by amino acids (partially) into glucose, which also keeps insulin levels up. That was Dr. Atkins one mistake, upping protein rather than fats.

Occasional intermittent fasting, in periods of at least 15 hours, also helps a great deal. According to the study charts, fat-burning doesn’t actually start in earnest until about 10-12 hours after eating, and then rises rapidly until about 15 hours after, then plateaus. Intermittent fasting is also far easier when satiety is high due to more healthy fat consumption, as opposed to fighting the constant hunger triggered by insulin.

Leptin and ghrelin play important roles, but the elephant in the room continues to be the obvious — insulin and its cycles. Check out Gary Taube’s book, “Why We Get Fat” where he goes through the over-100 years of research and makes it accessible in lay terms. For intermittent fasting, including all the study data and charts, see the work of Dr. Jason Fung, especially his 6-part youtube series, lectures to medical residents, called “The Aetiology of Obesity”. And perhaps the best, quick video (also on youtube) for just regular folks, is

one from Dr. Eric Crall called “Ketogenic diet video” outlining how to do an LCHF diet correctly, potential mistakes, and the science of why.

In our society, with insulin resistance skyrocketing, much of it hidden with 40% of pre-diabetics being thin and thinking they have no problem (plus nursing an unfounded attitude of moral rectitude for their thinness), whether or not a ketogenic or LCHF diet is chosen or intermittent fasting is practiced, it behooves everyone to understand the cycles of insulin, the risks of too much protein, and the benefits of raising dietary fat considerably.

Yes, much of what you say

Yes, much of what you say about carbs and insulin is essentially true, and Jon has said the same thing many times. But it is not relevant to this article’s key points:

And really? Exercise does very little to burn fat? We’ve never heard that before. Exercise burns calories. If you burn more calories than you consume, regardless of where those calories come from, then the calories you burn during exercise have to come from your body’s calorie reserves—i.e., your fat. It’s kind of like a conservation of energy thing. What studies are you referring to that indicate if you are exercising enough, you don’t burn fat? Now, that doesn’t mean that other factors don’t influence your resting metabolism. But resting metabolism and exercise are two different things.